30 years ago, Bristol saw a new chapter in music history opened.

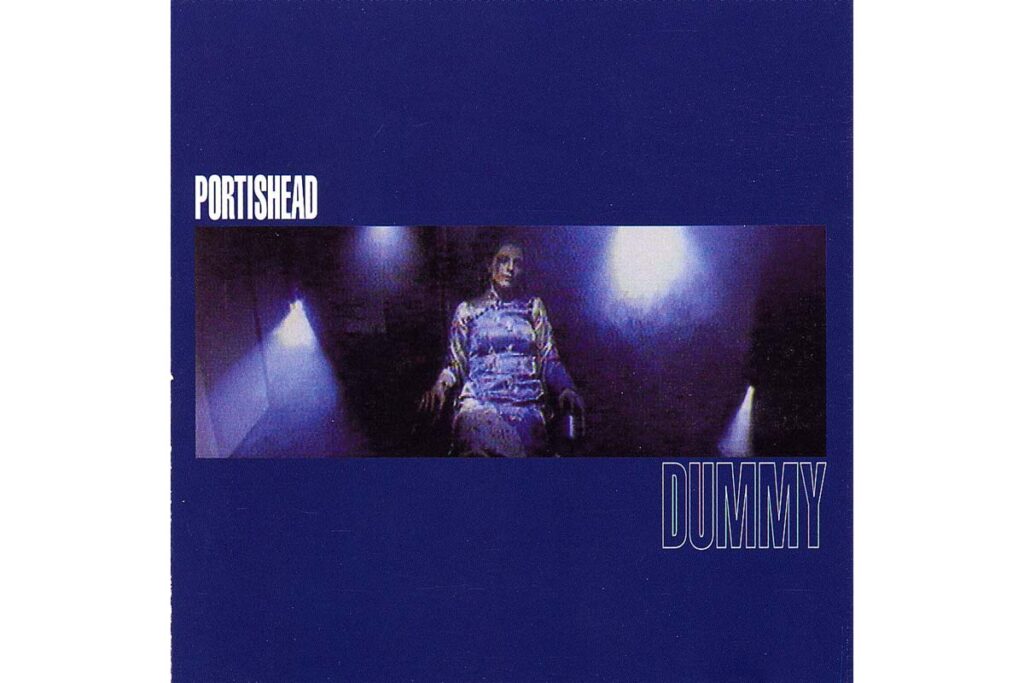

It is always tricky to precisely pinpoint the beginning of an era, the chronological origin of a musical genre. Too fluid are the transitional processes, too complex are the artistic exchange processes that lead to a new unifying element. In most cases, some timeframe serves as orientation, to which a subsequently iconic release can be attached, or when the term is first recorded in writing. In the case of trip-hop, both can be dated to 1994. In the June issue of Mixmag, music journalist Andy Pemberton coined the term “trip-hop” to describe the “head-bobbing” beats of DJ Shadow and the early Chemical Brothers. The decicive date was October 1994, however, as this is when the previously unknown band Portishead released their debut album Dummy, which won the famous Mercury Prize the following year.

The success of Dummy is ultimately based on the fact that the musical trip-hop ingredients used up to that point appear here for the first time focused like light through a magnifying glass. Added to this is the fragile voice of Beth Gibbons, which characterizes the atmosphere of the music like no other voice before it. But what are the hallmarks of the musical power of this genre? The rhythm in trip-hop is based on the breakbeats that have dominated since the late 80s, but often drags them out to infinity at a mere 80 to 100 bpm. Changing accents and stumbling “pause beats” lend the rhythmic texture an unpredictable irregularity that has a strong hypnotic effect. The beats are often interrupted or rhythmically counterpointed by scratching effects borrowed from hip-hop, which, unlike in hip-hop, are primarily intended to have a sound-aesthetic effect. This also includes the samples of groove noises from old scratched records that are mixed into almost all trip-hop albums, which brings us to another technical element that always adds a pinch of retro to the music alongside all the contemporary modernity: A special selection of sampling and sound collages – from jazz records to movie soundtracks to field recordings. The manipulation of these samples often results in unmistakable, quirky sound signatures. Portishead’s Dummy has also been a style-defining influence here: For example, you can hear Lalo Schifrin’s “The Danube Incident” and Smokey Brooks’ “Spin It Jig” on “Soir Times” – probably the album’s best-known track – as musical references. Also noteworthy is the sample in “Mysterons”, which comes from the British science fiction series Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons from 1967. The song captures the eerie atmosphere of this series, in which the Mysterons are depicted as invisible aliens communicating with distorted voices from radio and television sets. The rhythmic use of this sample in the first track sets the overall atmosphere of the album. Here again, Dummy can stand pars pro Toto for many trip-hop albums. The combination of various sound elements, including beats, samples, instrumentation and effects, establishes the atmospheric as the main musical category. Reverb, echo or distortion effects are often used to create additional depth and texture. The use of minor chords also contributes to giving the songs that specific dark and melancholy note, which never drifts into kitsch due to the electronic beats.

To properly understand the essence of trip-hop, however, you have to travel to Bristol. On the surface, you might think that the melancholy of the music is due to the constant rain in the south-west of the British Isles. But the roots go deeper into the special subculture of the late 80s and early 90s. Bristol has produced some of the most innovative and influential artists ever, who don’t fit in at all with the typical guitar sound of BritPop. From trip-hop pioneers like Portishead and Massive Attack to drum’n’bass geniuses like Roni Size, the city has undoubtedly made music history. But this creative melting pot that shaped the city’s sound in the 90s didn’t happen overnight. Bristol was already a center for musical experimentation in the early 80s. Bands like Pigbag and The Pop Group mixed punk, jazz and funk, creating a whole new sound that laid the foundations for what was to come later. The St. Pauls district played a crucial role in the development of the local music scene. Here, in the midst of the early English street battles of the time, experimental artists came together to play fat bass sounds in the Black and White Café. In this scene, ethnicity didn’t matter – it was all about the passion for music. DJ and graffiti artists from the so-called Wild Bunch collective, inspired by hip-hop, mingled in the Dug Out Club and amalgamated to form a scene from which the members of Massive Attack would later also come. Trip-hop, with its roots in Bristol’s diverse culture, is more than just a musical genre. It is the expression of a generation that has forged an extraordinary path and created extraordinary music through the fusion of different musical, cultural and social influences. And even after 30 years, it has to be said that albums such as Portishead’s Dummy rightly enjoy cult status, as they are an expression of timeless musical quality.