Delving into the psyche of one collector’s reflection of amassing such an assemblage of records that rarely get played

Musings About the 45-RPM Single was originally published in Copper Magazine issue 207

FIDELITY cooperation with Copper Magazine

Read this article also on Copper

Larry Jaffee is author of Record Store Day: The Most Improbable Comeback of the 21st Century (Rare Bird Books, 2022). For more information, visit www.larryjaffee.com.

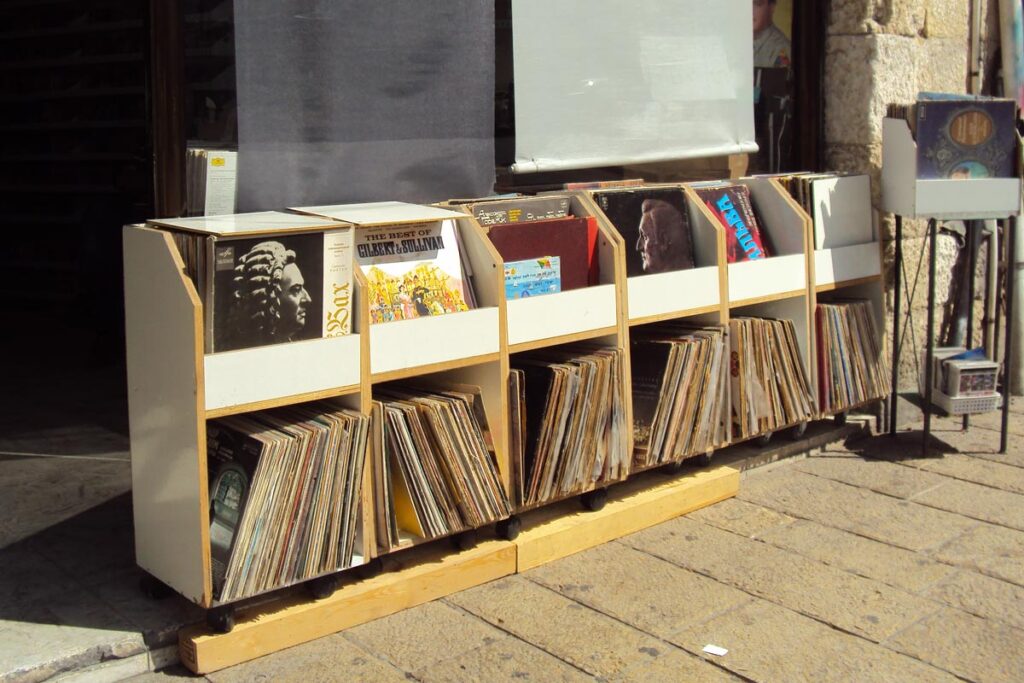

It takes a special crate-digging mood to go through a haphazard stack of scratchy, often-sleeveless, 45-RPM singles found in a record or thrift store to find those gems akin to a needle in a haystack.

In January 2021 a pop-up store that’s still there three-and-a-half years later opened a block away from my apartment in Upper Manhattan on Riverside Drive. It contains the former belongings of a collector of all kinds of books and records who passed away of COVID in the summer of 2020 and on his deathbed donated them to a non-profit community bookstore.

After making at least a dozen trips that yielded several hundred LPs over the next nine months, finally one day I turned my attention to the 50-cent singles, which landed a bonanza of beloved one-hit wonders from the 1960s to 1970s for a very reasonable sum. To name a few of the dozens acquired that day, reflecting my eclectic tastes: Mungo Jerry’s “In the Summertime”; Tommy Edwards’ “It’s All in the Game”; The Marmalade’s “Reflections of My Life”; The Angels’ “My Boyfriend’s Back”; The Idles of March’s “Vehicle”; The Status Quo’s “Pictures of Matchbook Men”; The Crazy World of Arthur Brown’s “Fire”; David Essex’s “Rock On”; Billy Swan’s “I Can Help”; Roy Head’s “One Night”; Kim Carnes’s “Bette Davis Eyes”; and Abba member Frida’s solo sole hit “Something Going On.”

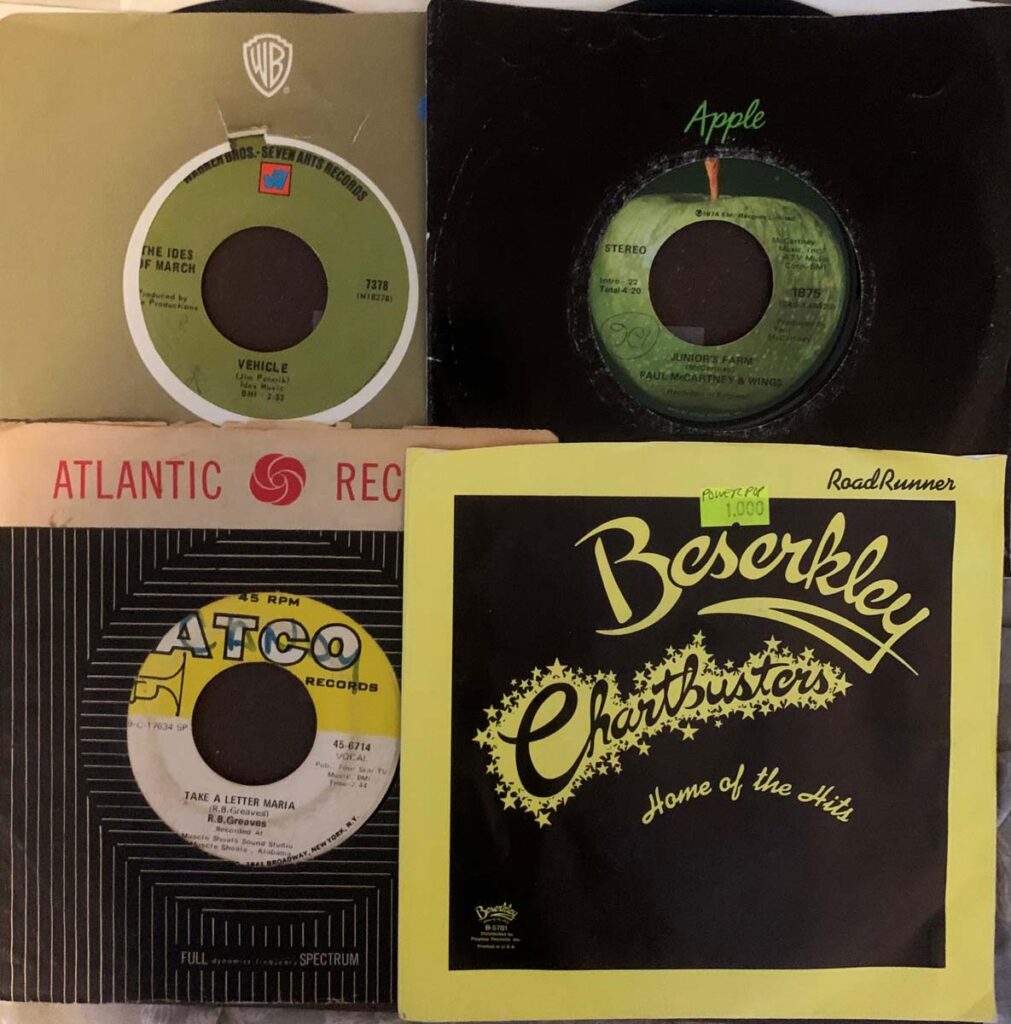

On that marathon hunting session at the pop-up store, which took several hours, I also bought original vintage pressings of chart toppers by perennial hitmakers, such as The Beatles’ “Something”/“Come Together” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand”/“I Saw Her Standing There”; Paul McCartney and Wings’ “Junior’s Farm”; The Zombies’ “She’s Not There”; Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale”; and Dionne Warwick’s “What the World Needs Now”/“I’ll Never Fall in Love Again.”

The haul also yielded Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams”/“Songbird” and “Sara”/“That’s Enough for Me,” and a promo-copy remix of the band’s “Sisters of the Moon” plus a longer version of the song by 26 seconds.

You might find this hard to believe but I’m not a completist, especially since nearly all of these songs already exist on LPs and CDs in my physical media collection.

When I started collecting records as a teenager, singles were important because I had less disposable income. Even then, back in 1973, I would buy a much-loved fluke hit that I couldn’t get enough of on Top 40 radio. Among my first 45-RPM purchases were Focus’ “Hocus Pocus” and ELO’s “Roll Over Beethoven,” both of which I remember blasting from my bedroom after having a fight with my mother.

Fast forward a half century: my 7-inch purchases now often come down to finding a cover version that I didn’t know existed, or an unusual song title.

For example, a visit last year to a Newark, New Jersey store not far from where I taught at Rutgers University landed me B.B. King’s rendition of the Lovin Spoonful’s “Summer in the City,” and the Intruders’ “(Love Is Like a) Baseball Game” by the formidable songwriting team of Gamble and Huff.

What the 7-inch, 45-rpm single provided during its 1950s to 1970s heyday and largely lost during the CD era was consumer empowerment: i.e., the right to buy a single song — and also get a value-added B side.

Ironically in the digital age, the single was brought back by Apple Computer’s iTunes, boiling down to the rhetorical question, and today’s streaming services:

Why buy a full album when really all you want is want the hit?

EMI in England certainly understood this nearly a half century ago, circa 1963 – 1970, with its year-round deluge of Beatles singles and EPs, while the insidious Americans over at Capitol would slice and dice the full albums because they wanted to pay less royalties, and then make new LPs out of all the extraneous tracks (e.g., Yesterday and Today, Hey Jude). And of course, the Yanks also put out plenty of American Beatles singles along the way.

My 45-single collection numbers probably a thousand and pales significantly next to my haphazardly-catalogued treasure trove of 4,000 LPs. Of course, that goes along with a thousand-plus CDs, at least 500 cassettes, and a hundred music DVDs and VHS tapes.

In the mid-1970s for a few months, I occasionally bought used 8-track tapes because the used car I drove – a blue AMC Hornet – came with an 8-track deck, and at garage sales I would pick up curios on the format such as a Kinks two-fer of The Kinks are the Village Green Preservation Society and Arthur or the Velvet Underground’s Live at Max’s Kansas City, which Lou Reed autographed for me in 2003. But then the deck and most of the tapes were stolen, so I let go of the potential 8-track obsession. (Thankfully, the Velvets and Kinks weren’t in the Hornet, and I still have them in my possession, as well as Jimmy Cliff’s soundtrack to The Harder They Come, also from that era of collecting.)

At record shows, I would pick up collectible laserdiscs of favorite movies, such as Bob Dylan’s Don’t Look Back or Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, even though I never owned a laserdisc player. It reinforces how I’ve always been format-agnostic. Among the few physical pre-recorded media formats I hadn’t collected to date are Edison cylinders and reel-to-reels.

During iTunes’ heyday, my full-album download purchases occurred only when I needed: a) immediate gratification, or b) the CD or vinyl was not available from Amazon and eBay, other online merchants, or brick-and-mortar stores. Falling in this category, I remember being frustrated in 2011 to only being able to get a digital download of Robbie Robertson’s then-new How to Become Clairvoyant.

Back to 45s, more often than not, in the 1970s and 1980s the 7-inch singles I often purchased were reissues – often with double-sided hits, or releases that never made it to a studio album, although could have showed up on a greatest hits compilation.

An example that comes to mind is Crosby Stills Nash & Young’s “Ohio,” which I bought about four years after it was released in 1970. At the time, I was amazed it was still in Sam Goody’s slim 45 bins. The obvious cover should have been the iconic photograph of the distraught teenage runaway standing over the body of one of the four Kent State students who were killed by National Guardsmen, instead of the nondescript uniform sleeve that the label used for reissues.

Those 45 singles in my collection that do have picture sleeves I most likely bought more for the artifact or music than the aesthetics. I couldn’t resist owning, for example, the German 45 pressing of “Whatever Gets You Through The Night” b/w “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” recorded live at an Elton John concert at Madison Square Garden, marking John Lennon’s last public performances. Too bad the photo of them is absolutely hideous.

I now think of the 45 picture sleeves that I once had in my possession but have no longer, such as Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane” for the then-jailed, middleweight boxing champion Ruben Carter (a photo of him adorned the cover), or Bob Marley’s “Zimbabwe,” which featured a photo of Joshua Nkomo, who led a guerrilla faction (longtime Zimbabwe dictator Robert Mugabe led the other) that toppled the former apartheid regime known as Rhodesia. That record I stupidly traded to a relentless completist Marley collector who wore me down, and gave me a Peter Tosh songbook in exchange. I’d frame that rare single today if I had it.

Speaking of reggae, I’ll spend hours searching for a single I know is somewhere in my non-organized collection when a reggae artist dies, such as Lee Perry, for example, whose 45s of “Return of Django” and “Iron Fist” hit my turntable as inspiration for a Facebook tribute post.

Let’s face it, singles, whether 7-inch or 12-inch, are a pain in the ass to buy – Discogs being an exception – let alone play, especially on a manual turntable. Of course, 78-RPM collectors have to make an even bigger effort to consume what’s emanating from the speakers.

I keep on telling myself that I’m going down this rabbit hole of 45-RPM singles collecting for the eventual purchase of a long-coveted jukebox. But the reality is, I don’t have the space in my already-extremely-cramped apartment to fit a jukebox. Nor do I think my neighbors would appreciate the added aural fidelity pounding through the walls. Also, a friend who has a jukebox says to be prepared to spend at least $7,000 for a machine that’s in good working condition and doesn’t’t need replacement parts.

Nevertheless, I still periodically peruse eBay’s listings and fantasize that it would be as good a reason as any to move into a house isolated in the middle of nowhere. Never say never: the things we do for the love of music!

Special thanks to Copper Magazine