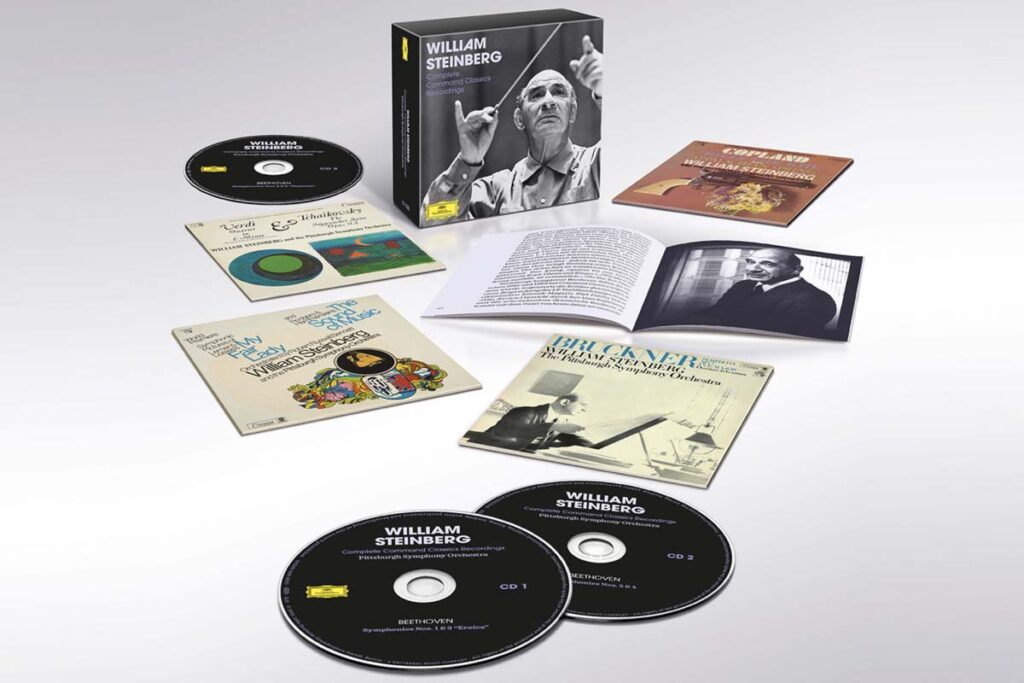

It is thanks to Deutsche Grammophon that the widely underestimated conductor William Steinberg has been brought back to the attention of classical music lovers. His legendary audiophile Command recordings with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra are now available in a high-quality, no-frills box set with 17 CDs, while three of his recordings with the Boston Symphony Orchestra appear in the vinyl series “The Original Source”.

William Steinberg was born Hans Wilhelm Steinberg in Cologne in 1899 and received the Wüllner Conducting Prize at the age of twenty. Soon afterwards, Otto Klemperer hired him as his assistant and supported him. In 1933, Steinberg was dismissed from his post at the Cologne Opera by the National Socialists due to his Jewish origins. He was rehearsing Ernst Toch’s opera Der Fächer when Nazi henchmen stormed into the hall and literally snatched the baton from his hand. Steinberg and his wife left Germany in 1936 and went to the British Mandate of Palestine before emigrating to the USA. Steinberg is best known for his long tenure as music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra from 1952 to 1976. From 1969 to 1972, Steinberg was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but retained his position in Pittsburgh.

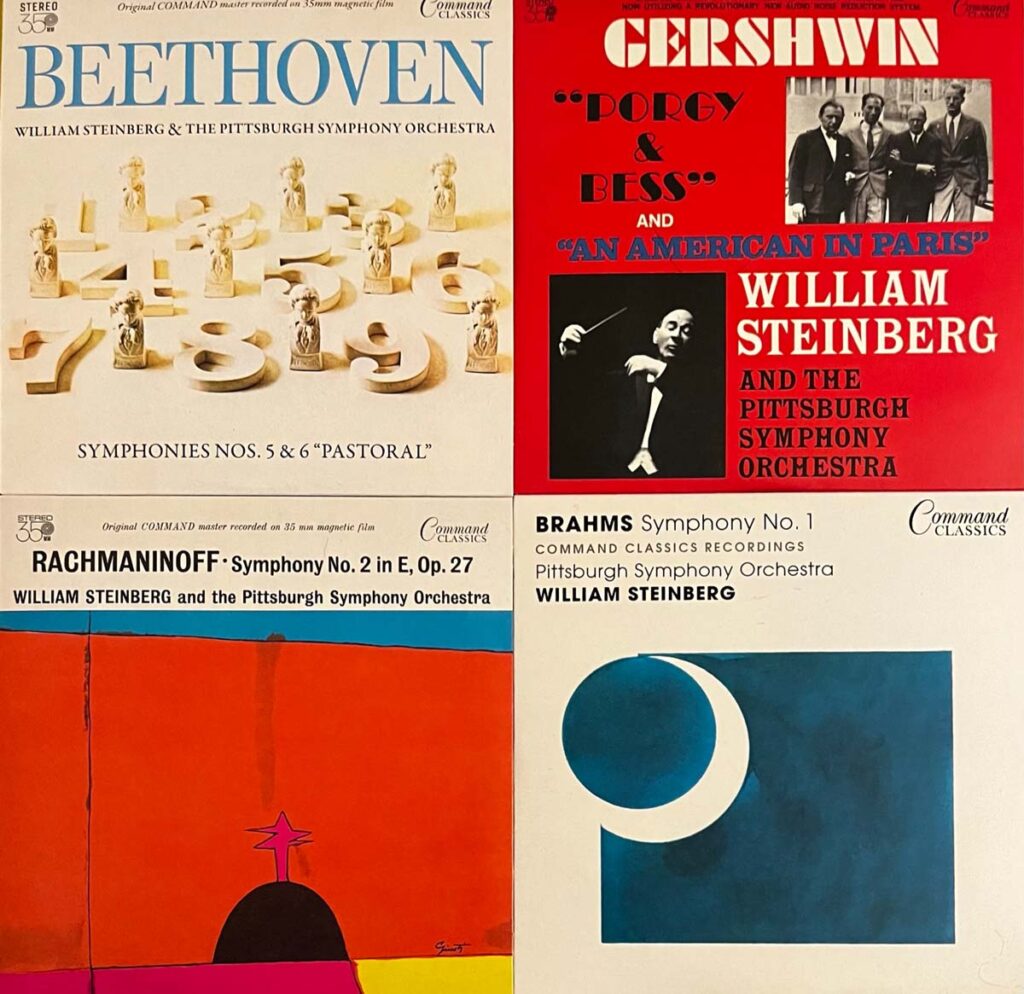

Command Records was founded in 1959 by Enoch Light and soon sought contact with Steinberg. While the rest of the record industry had made magnetic tape the standard for vinyl recordings, Command’s albums were recorded on 35-millimeter film. Light utilized the width of the film strip to create multi-track recordings, as opposed to the more limited two or three tracks offered by most recording studios at the time. The slightly higher linear speed offered an advantage in analog fidelity, and the sprocket-driven film mitigated wow and flutter. This allowed Light to record more instruments individually and adjust their input levels. If you want to grasp Steinberg’s specific way of interpreting these audiophile recordings, it is worth listening to the recordings of classical-romantic symphonic music first. Steinberg follows the composer’s metronome markings in almost all movements of the Beethoven symphonies, avoiding tempo fluctuations and agogic liberties for the most part. Steinberg draws Beethoven’s energy solely from the musical text – it is a completely unpretentious but very effective way of playing music. He also removes the heavy Germanic style from Brahms’ symphonies. There is an adage among musicologists that the permanent modulation work in Brahms’ music always makes you think of the founding of Krupp-Stahl … None of this can be felt here with Steinberg. Not just that – at times he almost makes Brahms sing and dance. The American pool of this compilation is at least as remarkable. Steinberg has always been passionate about performing composers such as Gershwin, Copland and Rodgers. The interpretative meticulousness and sense of rhythmic complexity and orchestral colorfulness that Steinberg displays together with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is admirable.

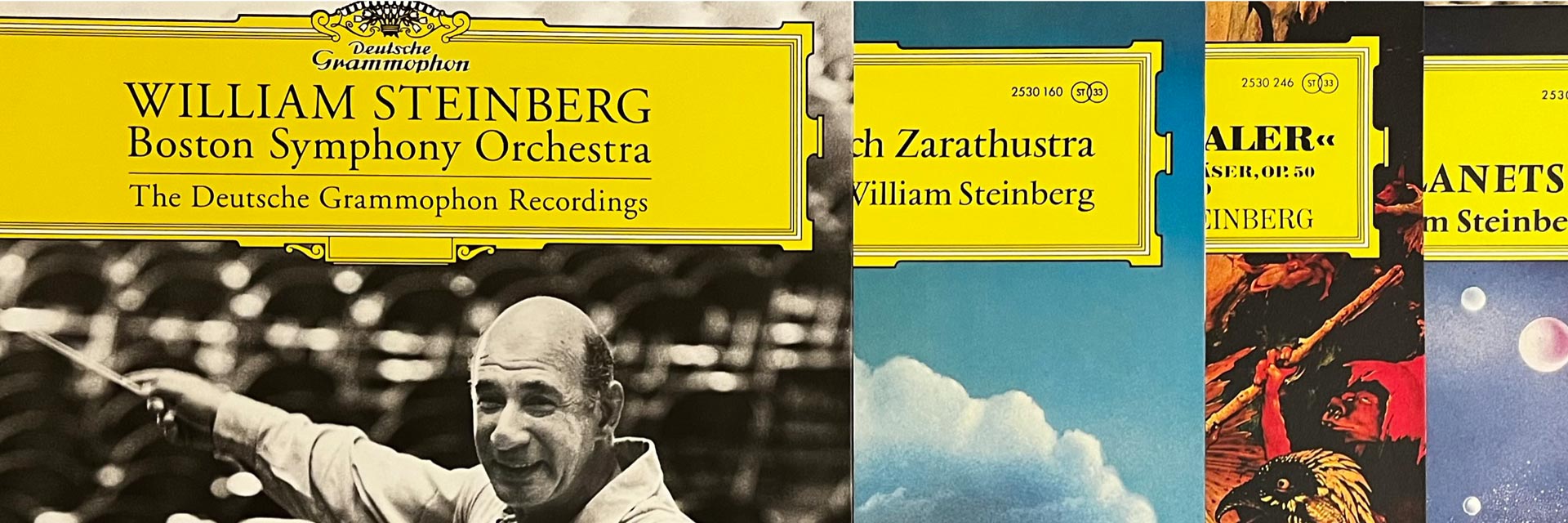

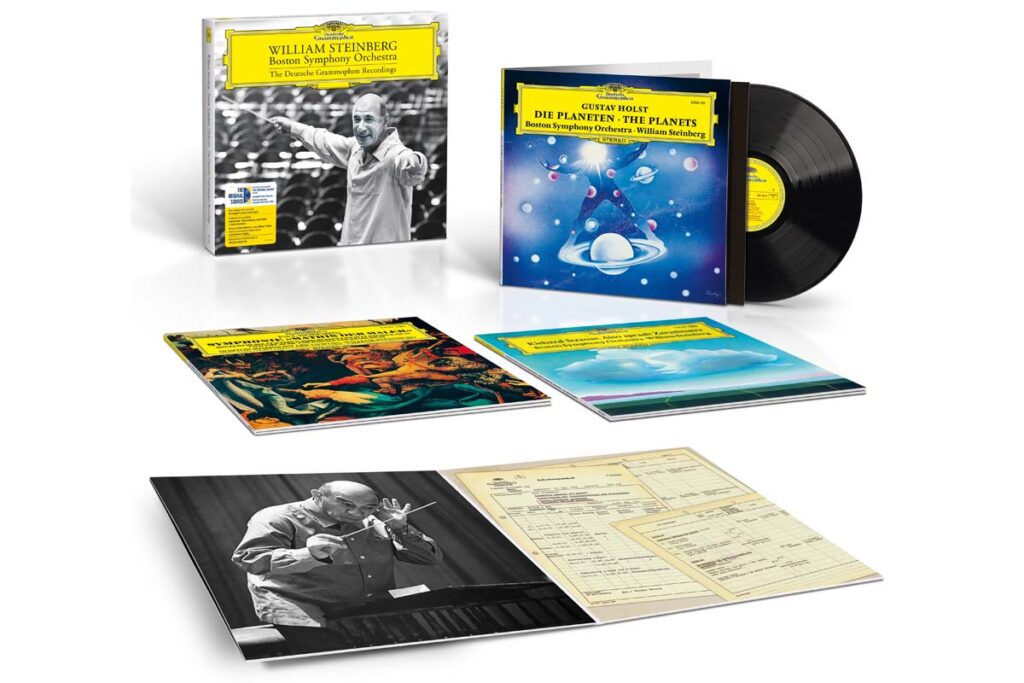

Let us now take a look at Steinberg’s Boston period. There are tangible reasons why the BSO’s recordings in the 1970s generally sound above average – they were productions that would no longer be feasible today for financial and organizational reasons. For example, the orchestra moved from the stage to the auditorium for a record production, which naturally required considerable rebuilding work. For a record production, however, better technical and acoustic conditions could be realized there, which would not have been possible when recording from the concert podium. As in Pittsburgh, Steinberg also stands for a straightforward and almost anti-metaphysical approach to interpretation on the podium of the Boston Symphony, allowing the music to speak for itself. It is impressive how he ploughs through Holst’s “Mars” in just six and a half minutes, not putting his own stamp on the brute war march in five-four time and allowing the brutality of the composition to speak for itself. The same applies to the jubilant pose of “Jupiter”, which does not drift into artificiality through arbitrary tempo fluctuations or agogic antics.

However, it may indeed have taken the reconstruction and re-release of the four-track tapes by the magical hands of Rainer Maillard and Sidney C. Schmidt to realize the potential of Steinberg’s art of interpretation. I know of no other recording that allows the sound of the bowed strings at the beginning of the Planets Suite to make its way into the ear so transparently, or that allows the brass to play with such a dynamic range. It was foreseeable that the fanfare at the beginning of Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra would become the ultimate loudspeaker test, at the latest with the final cymbal crash; thanks to Steinberg’s interpretation and the recording quality, the composition’s fine polyphonic soundscapes can also be heard in an excitingly new way. However, the insider tip of this 3-LP box is Hindemith’s Concert Music for String Orchestra and Brass op. 50, a work commissioned for the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the last of three works with similar titles from the years 1929 to 1930, which are played and heard musically despite Hindemith’s harmonic sophistication and structural differentiation. Here, too, Steinberg’s disinterested conducting ensures a more than adequate artistic approach, which emphasizes the baroque structures rather than the large orchestral habitus of the composition.

Whether on CD or vinyl, Steinberg’s recordings from Pittsburgh and Boston are sonic and interpretative masterpieces that still set standards today and are now available again thanks to DG.

William Steinberg & Boston Symphony Orchestra – The Deutsche Grammophon Recordings

Holst, The Planets, Strauss, Also sprach Zarathustra, Hindemith: Mathis der Maler, Konzertmusik für Streichorchester und Blechbläser I Deutsche Grammophon „The OriginalSource“, 3-LP-Box

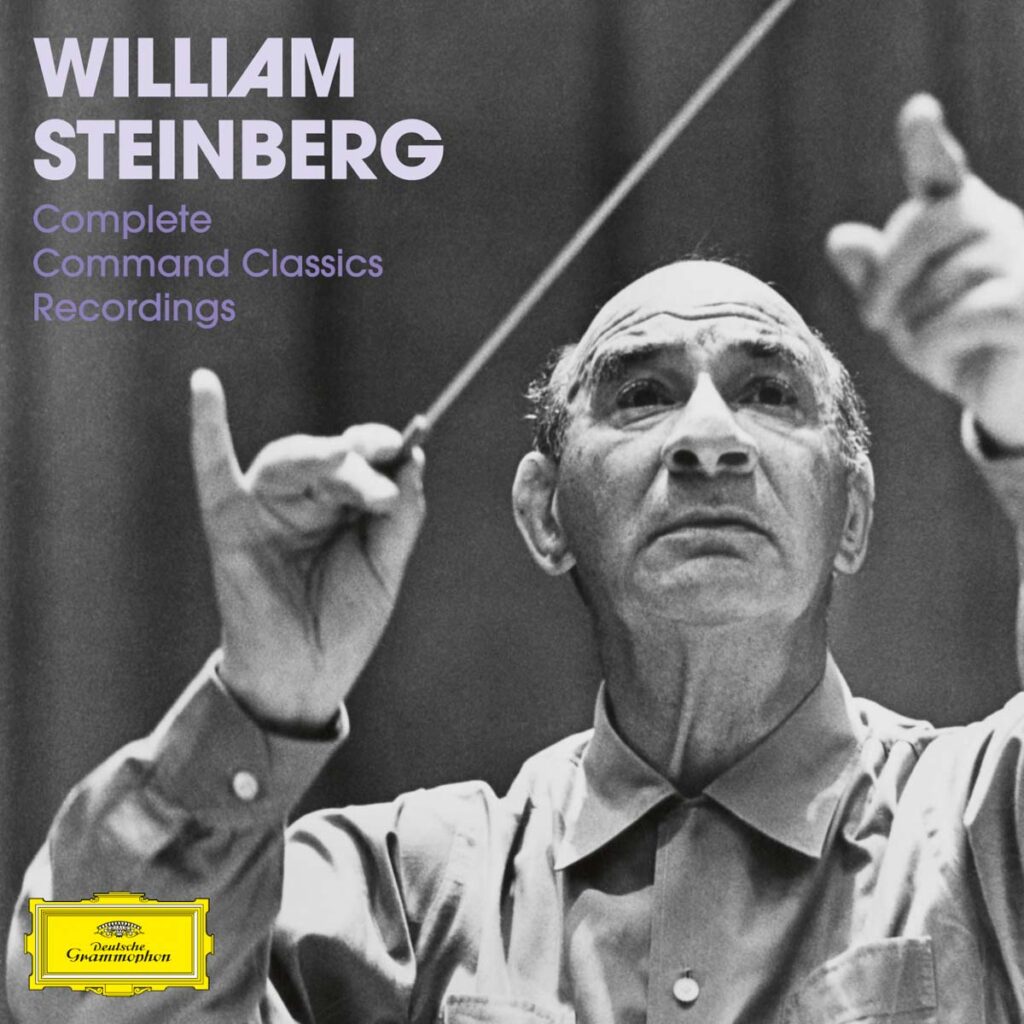

William Steinberg – Complete Command Classics Recordings

Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Wagner, Copland, Gershwin, Schubert, Rodgers, Strawinsky, Schostakowitsch u. a. I Deutsche Grammophon, 17-CD-Box