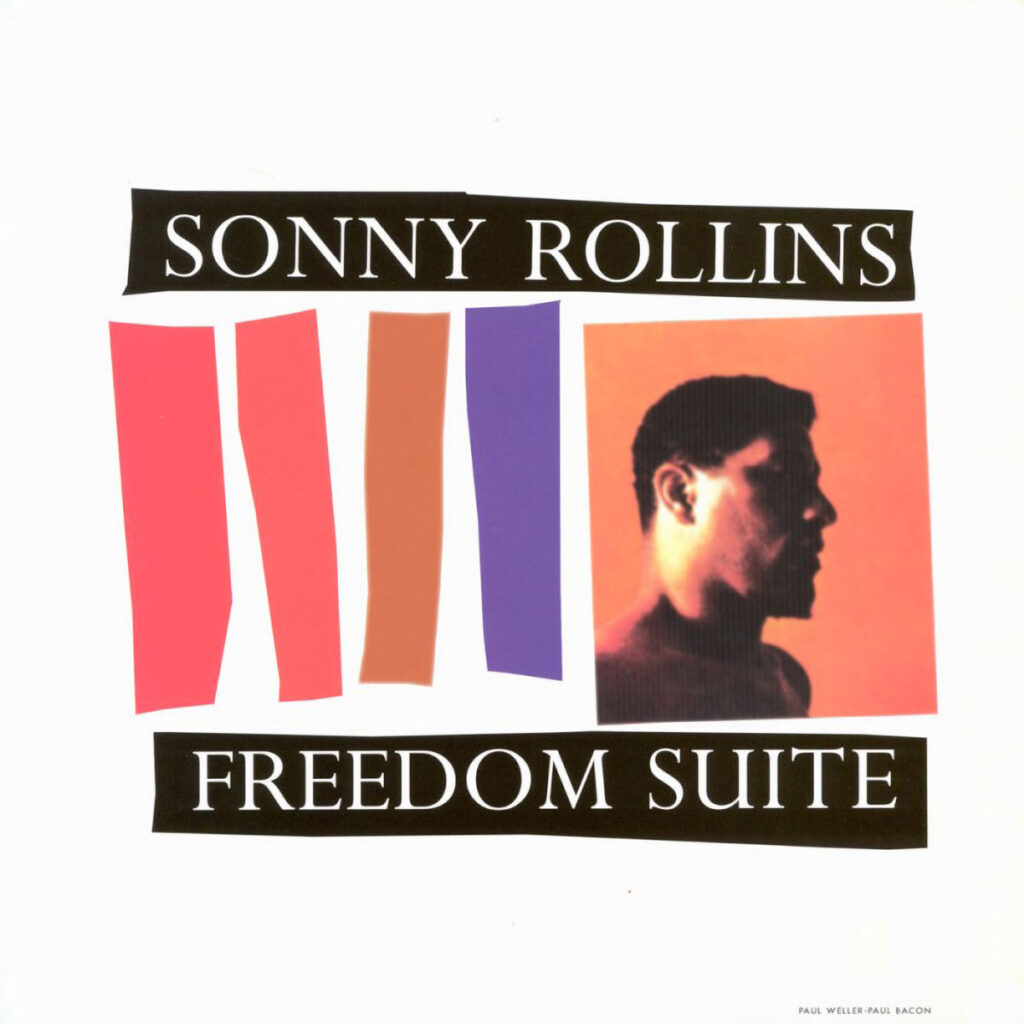

As early as 1956, Sonny Rollins was regarded as the leading saxophonist in jazz – and little has changed to this day.

He began his career as a young sideman for bebop pioneers such as Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro and J.J. Johnson. He then made a series of important leader records: Plus 4 with the Brown-Roach-Band, Saxophone Colossus in a quartet, The Bridge with Jim Hall or Sonny Meets Hawk with Coleman Hawkins. On no album, however, can Rollins be heard more concentrated and essential than on Freedom Suite, accompanied only by bass and drums. Since this record, the piano-less trio has been regarded as Sonny Rollins’ very own format.

What is special about Rollins is not only his powerful, sonorous, loud tone on the tenor saxophone, but above all the way he uses this tone, the way he blows it on and off – unorthodox and provocative. His themes are at their core laconic and simple, his improvising has something of a deliberately careless saunter, following the theme rather than the chords. Then again, however, he interrupts this nonchalance with willful motifs and quotations out of nowhere. This is evidence of sardonic humor and great self-assurance – the spirit of jazz.

“Freedom Suite” – this is also the name of the A-side of the album, a piece almost 20 minutes long, the ‘heart of the record’. True to the title, it forms a five-part “suite” – with a strong first movement (7:55), a waltz theme with an out-of-tempo ending (1:05), a ballad improvisation (6:12), the waltz theme again (1:05) and an up-tempo finale (3:13). All themes have Rollins’ typical brevity and simplicity and are closely related to each other. The saxophonist makes use of the harmonic openness of the piano-less instrumentation and demonstrates in every bar what improvisational sovereignty means. He gives his fellow musicians room to develop and solo. Oscar Pettiford was the most melodic bassist of modern jazz, Max Roach the most sensitive of all drummers. A major work with minimal equipment.

The title “Freedom Suite” naturally refers to the musical freedom of jazz and especially the piano-less format. The title also refers to the inner freedom of improviser Sonny Rollins. But beyond that – as Rollins makes clear in the accompanying text – he is thinking of the African-Americans’ aspirations for freedom. Since the official abolition of racial segregation (“de-segregation”) in 1954, the black freedom movement has gathered momentum. There was the Montgomery bus boycott, the Little Rock conflict, riots in Harlem and lawsuits over racist laws in the southern states. “America is deeply rooted in black culture,” Rollins writes: ”the vernacular, the humor, the music. How ironic that the black man is rewarded for this with inhumanity.” The Freedom Riders and free jazz came a few years later. But Freedom Suite heralds both. Rollins’ fellow musicians Pettiford and Roach were among the most politically explicit musicians in jazz.

The political album title met with resistance in the white jazz world at the time. The record company quickly withdrew the album from circulation and re-released it under the title of the last track on the B-side: “Shadow Waltz”. On this B-side, Rollins’ trio covers four pop melodies from Broadway, pieces from the years 1930 to 1957. This is also typical of Rollins: this unagitated, non-chalant way in which he simply transforms bland (white) musical or film songs into pithy (black) jazz. That, too, was, of course, a message.

Sonny Rollins – Freedom Suite on discogs.com