A discographic tribute to the pianist of the century Maurizio Pollini

Maurizio Pollini has passed away. He outlived his friend and colleague Claudio Abbado by exactly ten years; and if Abbado’s death was a centennial quake that shook the conducting world, it is now the world of pianists that is shaken by a quake of equal magnitude, as well as the musical world in its entirety. It is always difficult to compare artists, let alone rate them against each other, but since the death of Glenn Gould 42 years ago, no loss has left such a vacuum in the music world as Pollini’s death.

Maurizio Pollini’s victory at the International Chopin Competition in 1960 marked the beginning of a career that was to be characterized by extraordinary technical ability and interpretative depth full of intellectuality. While his time at Helidor saw the release of only a handful of Chopin recitals in the 1960s, his discographic output increased rapidly after signing a contract with Deutsche Grammophon in 1972. Initially, Pollini released an average of two recordings per year with the yellow label. Of course, Chopin recordings marked the beginning here as well. And yet, the way Chopin sounds here is revolutionary for the time, far removed from the bliss of bourgeois salons. Pollini sweeps through the collected etudes with strict clarity in his first DG release. No kitsch in the slow etudes and unbridled power without dragging out rubati in the fast pieces. That wasn’t just something new in 1972 – back then, it was downright monstrous. His recording of the Préludes op. 28, released in 1974, was grandiose in the way he let Debussy peek around the corner in the G major Prélude, for example, and let popular hits such as the E minor Prélude pass by in quiet grandeur, eschewing sentimentality. What follows in the subsequent releases is the great classical-romantic canon between Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann, whereby each recording is provided with an individual exclamation mark, be it Schubert’s “Wanderer Fantasy” in 1974 or Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier Sonata” in 1977.

It is impressive how uncompromisingly Pollini has championed the music of the 20th century; Luigi Nono was still on the program in his last concert in the winter of 2023. This also applies to his contract with Deutsche Grammophon from the very beginning. Immediately after his release of the Chopin Etudes, he produced an LP with Stravinsky and Prokofiev, and would go on to take things to the extreme with a CD edition featuring Webern and Boulez. The stupendous technique with which Pollini rushes through Stravinsky’s hustle and bustle at breathtaking speed, while still always having an eye for the ironic moments in the music, is magnificent even today. In 1974, the politically and musically revolutionary trio of Maurizio Pollini, Claudio Abbado and Luigi Nono made their first discographic appearance. All three were associated with the Italian and international left and did not shy away from performing for the working class or engaging in discussions with critical students. Como una ola de fuerza y luz, the main work on the LP, is dedicated to the late Chilean revolutionary Luciano Cruz and shows how Nono, in his peculiar dichotomy of intimate beauty and brute sonic eruptions, composed the work to suit his friend Pollini’s hands, so to speak.

What’s striking is how Pollini could never be persuaded to record rushed complete editions. His complete edition of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, which was only released in 2014, was created over a period of 40 years. And yet it comes across as perfectly homogenous, possibly because the young Pollini has always carried in him the serenity of an old soul while the aged, mature pianist has always remained Sturm und Drang at heart. A good 20 years also lie between the recordings of the first and second volumes of Debussy’s Préludes; “Everything in its own time” seems to have been Pollini’s motto, he never allowed himself to be pressured into anything by his record company, he was immune to the desires of the commercial music market in his very specific way.

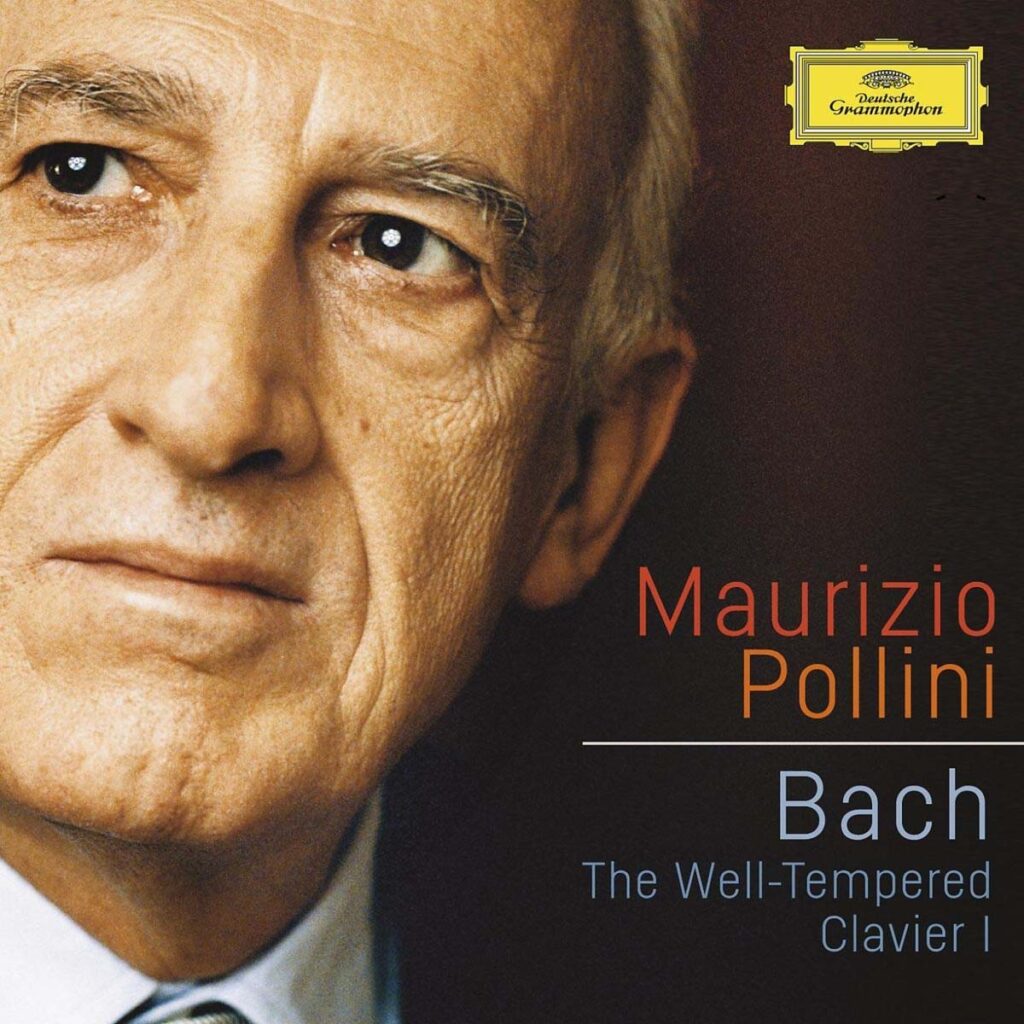

It took Pollini a long time to devote himself to Bach. Even though he occasionally performed parts of the Well-Tempered Clavier in concert, almost 50 years had passed after the beginning of his career at the Chopin Competition before he would record the “Bible of Piano Playing” in 2009, albeit only the first volume. This was also to remain his only Bach recording; no French Suites, no Partitas, only the Well-Tempered Clavier can be found in his discography. In an almost playful manner, Pollini clearly chisels out Bach’s structures without exaggeration. This can be heard wonderfully in the non-legato playing of the fugue in C minor, which sounds much more pointed and choppy with many other interpreters. It is this contrasting way of playing that makes this recording so worth listening to.

And finally, one last Beethoven: in 2022 Pollini once again recorded the sonatas op. 101 and op. 106. There is no softness of age to be found in the interpretation, quite the opposite. The tempi are more forced than in the first recording in 1977, the arcs are presented in an even more straightforward way – this recording sets a final exclamation mark.

We bow to a pianist whose extraordinary technical precision enabled him to navigate through complex structures and textures with apparent ease and interpret them with profound musical understanding.

Discographical note: An overview of Pollini’s recordings can be found at www.discogs.com. As countless reissues with different combinations of works have been released over time, we will not provide specific recording references here.