Africa, Africa, again and again.

His father, a follower of pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey, had already impressed upon him at a young age: “You have to go to Africa one day, to our motherland.” In addition to jazz, Randy Weston’s early listening experiences included music recordings from Africa. “This music opened up something inside me and I couldn’t get enough of it,” he said. In 1961, the time had finally come: the 25-year-old jazz pianist was invited to Nigeria as part of a delegation of African-American musicians and poets. And after that he traveled to “Mother Africa” again and again – in 1967 also with his own band, with which he visited 14 African countries. At the end of this tour, Randy Weston settled down in Tangier, Morocco, where he had played the last concert. He stayed for five years, studied the music of the Gnawa masters, founded a music club and organized the first African jazz festival in 1972. Later, he also played at music festivals in Tunisia and Nigeria. He refused to choose between West and North Africa: “I claim the whole continent for myself.” Randy Weston brought Americans to Africa and Africans to America and didn’t forget the African diaspora in Brazil, Venezuela or Cuba, either.

This pianist listens to and plays jazz “the African way”. When transposing his music to suit the “European” piano, he was taking inspiration from the playing of his colleague Thelonious Monk, with whom he had already become friends in the 1940s. “When I heard Monk play, I realized that this was the direction I had to go in. He played the way they must have played in Egypt 5000 years ago. I hear ancient Africa in his music. He approaches the piano from an African perspective – with polyrhythms and question-and-answer forms. And he plays with outstretched fingers – not the way you’re being taught.” The percussive touch, the thundering basses, the unwieldy polyrhythms of the phrasing, the clashing dissonances and the harmonic-modal openness in Weston’s playing are always reminiscent of Monk. But Weston’s playing is technically more virtuosic, musically more complex, formally more open and more spontaneous than his role model. At times he seems to transform himself into an entire drum orchestra. “We are the people of the drum,” says Randy Weston. “When I play the piano, the piano is also a drum.” Saxophonist Billy Harper said: “He’s unlike any other musician I’ve played with. He’s transcended thinking in technical terms.”

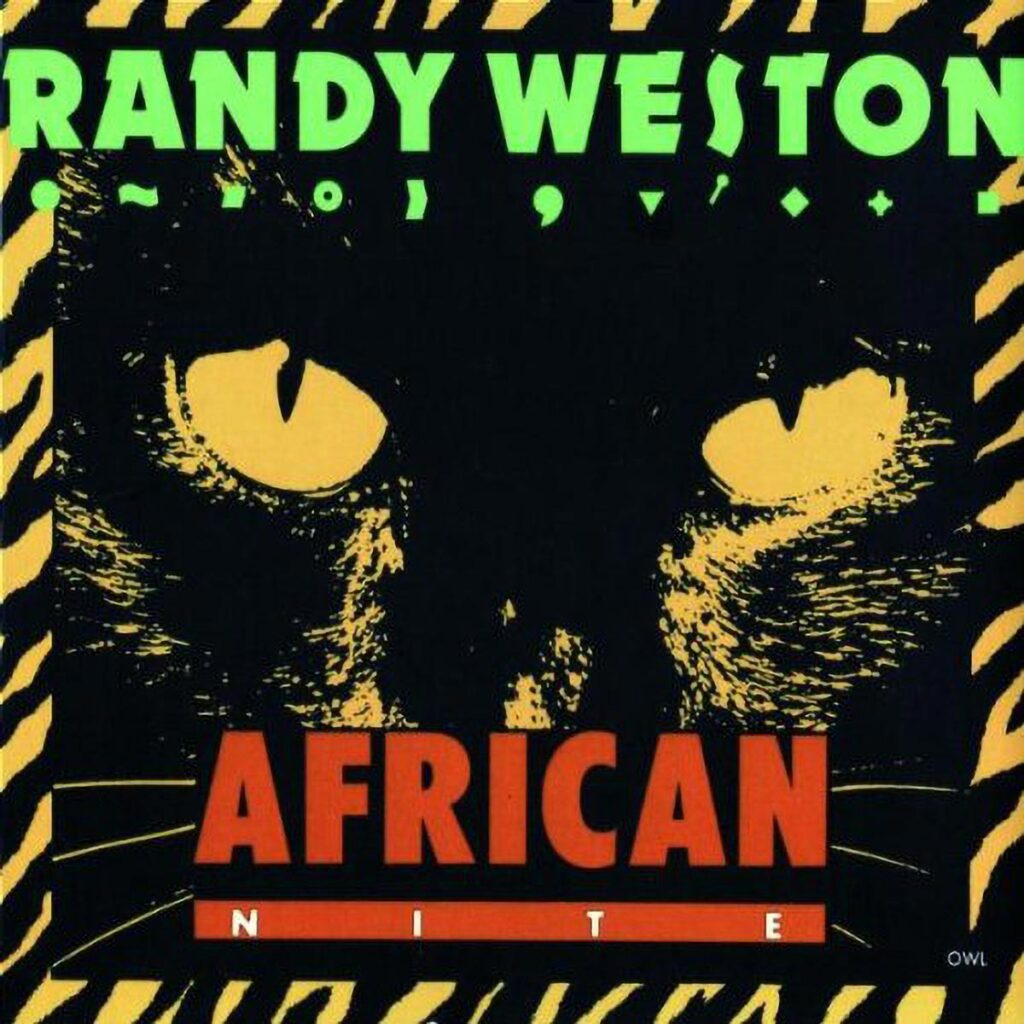

In 1975, Randy Weston was still flying high on his time in Morocco. He didn’t need a band, he had everything ready at the piano, the sounds, the moods, the smells. “Yubadee” is dedicated to a Gnawa musician with whom he had spent several months. He wrote the title track “African Nite” on a magical evening in Tangier, sitting alone at a large Bechstein grand piano. “Jejouka” salutes a legendary music village in Morocco’s mountains, whose Rhaita winds are said to cure mental illness. These solo pieces on the piano combine blues and guembri fantasy, African drums start to bop, Arabic melodic phrases get their own swing. The “Blues For Senegal” – reminiscent of a guest performance in Dakar in 1967 – seemingly effortlessly combines the spirit of several continents. Africa is in everything: “If you take the African elements out of bossa, samba, jazz, blues – there’s nothing left,” says Weston. There may be wilder, more exalted, louder albums from him. On African Nite, he translates it all into refined pianism, delivering an inner, subjective concentrate. Africa, Africa, again and again.