Covering normally refers to songs being performed by other artists, but actual album covers attract their share of impersonators, too. The covered cover: Is it a witty reference, respectful homage or parody? Or is there a deeper meaning behind it? Up now: Thelonious Monk versus Ken Thomson.

Not only did Frank Zappa record music by a historical namesake (s. FIDELITY print magazine No. 40), so too did jazz pianist Thelonious Monk. To kick off his 1957 album, Monk’s Music, he arranged an old hymn composed by English organist William Henry Monk (1823–1889). “Abide With Me” is 54 seconds long and arranged for four wind instruments, although the rhythm section (including Thelonious Monk himself) takes a break. Despite this composition by another composer, the title of the album is correct. The record does actually contain just music by Monk — any Monk.

You just have to grasp the opportunity when it presents itself. When do you ever get four wind instrument players in one studio at the same time. For this session Monk insisted on having all of two special tenor saxophonists. One of them: Coleman Hawkins, a former mentor, in whose band Monk cut his first recordings in 1944. The other: John Coltrane, his most recent pupil, who had been fired by Miles Davis shortly beforehand — Monk had witnessed this. Hawk and Trane — two tenor saxophonists, who symbolized the past and the future. The one had his roots in the 1920s, in the pre-swing era — while the other was a pioneer of free jazz. Monk was the bridge — he was able to sound like a stride pianist as well as do the avant-garde proud. Coltrane called Monk a “music architect of the first order”. He even learned new saxophone tricks, circular breathing and harmony techniques from the pianist. “Monk forced me to play a huge number of choruses around an ever-identical theme, in order to find new ideas.”

Monk’s Music is a kind of an all-star session. “Well You Needn’t” (Coltrane is the first soloist), “Ruby My Dear“ (a feature for Hawkins), “Off Minor” and “Epistrophy” — the tracks on the album were practically classics. Monk had already cut them during his first vinyl recordings in 1947/48. Only this time the themes had been specially arranged for the four wind instrument players (the most involved one: “Off Minor”), while the flow of the tracks makes you think of a relaxed jam session. The soloists are given space — and nobody is giving the others a hard time. A new composition by Monk only says hi right at the end: “Crepuscule With Nellie”, perhaps intended as a counterpart to the opening hymn. Monk’s wife Nellie at that time was in hospital, outcome uncertain; the composition was an appeal to fortune — and it helped. The first recording of the ballad only presents the theme, there is no solo. Even later on in this composition Monk never allowed any improvisation, because he was superstitious.

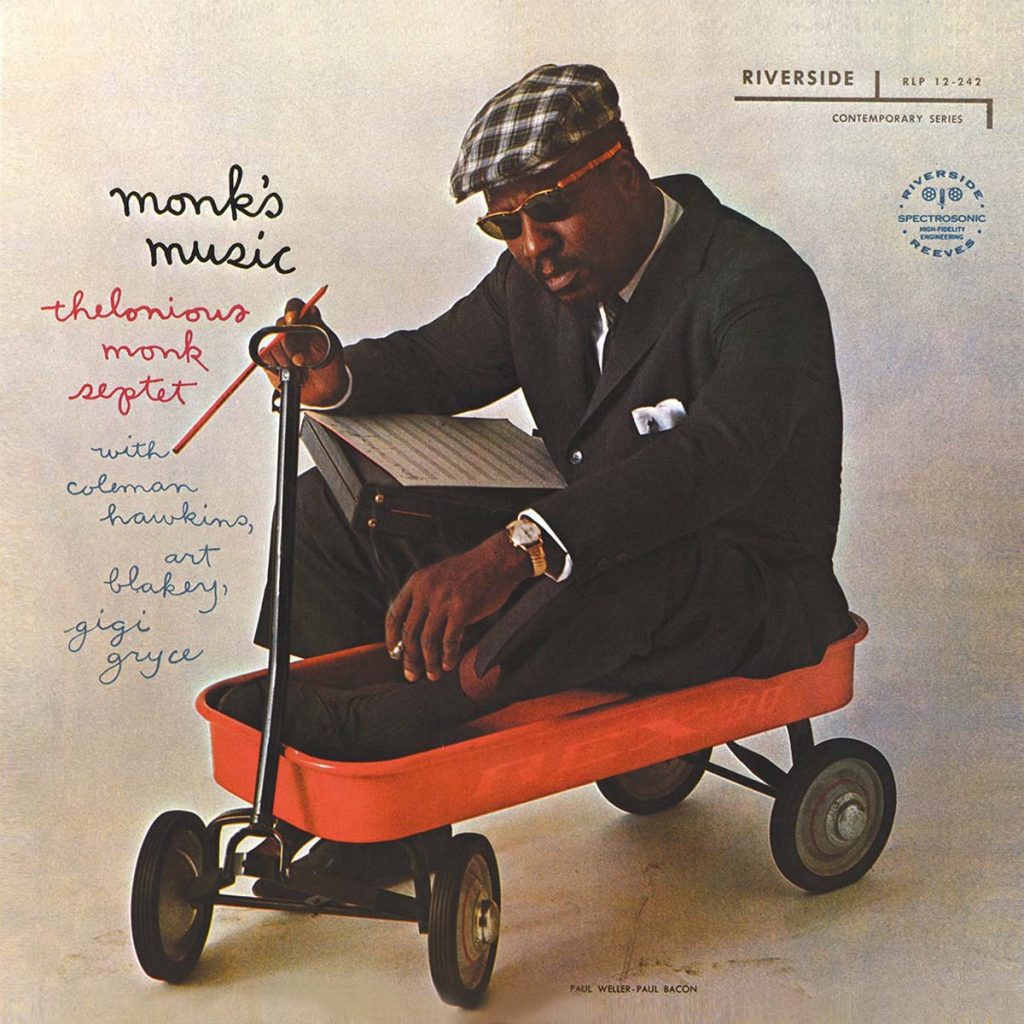

The producers often came up with the craziest ideas for Monk’s album covers. Nothing appeared too bizarre to visually highlight what a most extraordinary genius and one-of-a-kind this Monk was. Monk in mirror image, Monk times five, Monk as a pilot or guerrilla fighter. For the cover of Monk’s Music they wanted to put him in a monk’s habit or in a tuxedo with a white tie. The pianist is said to have replied: “I would prefer to pose on my son’s handcart, because that’s where I sat when I recently had the urge to do some composing.” You can’t dream up a more bizarre motif. But: it’s unlikely that Monk also wore sunglasses and a checkered cap when composing.

Four wind instruments — two woodwind and two brass — also feature on Ken Thomson’s new album, Sextet. Whether this lineup was inspired by Monk’s Music or whether Thomson was simply reminded of Monk’s album at one time or another — it doesn’t matter. At any rate, a modern jazz musician can’t go wrong with a reference to the former architect of avant-garde jazz, even if it is only a cover motif reference. However, the way the little red cart is standing there all on its own on a white background, is hovering, is materializing is of course a little iconic. It reminds you of Warhol’s Banana. Or of Warhol’s Soup Can. Such references would dovetail with Ken Thomson. The man not only plays a mean punk jazz jug (in common parlance: alto saxophone), but is also at home on the New Music and performance art scenes. He plays clarinet with the Bang On A Can All-Stars, writes for the American Composers Orchestra, and collaborates with eMusic composers.

The 42-year-old sometimes calls his style “21st Century Third Stream”. On the album, Sextet, he and his five colleagues astound the listener with music that ranges between high-performance improvisation and the musical language of contemporary concert music. A fast and furious jazz drive features the ingeniously merged voices of the wind instrument players. Only seldom do you hear music on a jazz album that is of such complexity and that is so expertly played. But to let people access the album Thomson did then draw inspiration from Monk’s Music. To parallel Monk’s adaption of the English hymn “Abide With Me” he put a piece by György Ligeti at the beginning — and indeed as an arrangement for four wind instruments too. “Passacaglia Ungherese” in its original form was composed for the harpsichord. A musical miniature. A humorous exercise. Alienated to a wind instrument chorale, Ligeti’s piece is transformed into a kind of sonorous Warhol.

Thelonious Monk: Monk’s Music | (Riverside RLP 12-242) 1

Ken Thomson: Sextet (Panoramic Recordings pan09)