Tenor saxophonist John Coltrane released about 40 albums as a bandleader during his lifetime. Among them Blue Train always took a special position – the only leader album that Coltrane recorded for the label Blue Note.

The label that was considered the epitome of hardbop. The label that showed real respect to the musicians and paid them several days of rehearsal before the recording date. The latter has mostly paid off musically – so also with Blue Train. The sextet acts with concentration, is “together”, plays with energy and temperament. “None of his albums swings more effectively than this one,” writes Colin Larkin. John Coltrane had borrowed the bassist and the drummer from Miles Davis. The two fellow wind players, on the other hand – both very young, 19 and 23 – he got from Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. The three horn players played a few club dates together before going into the recording studio for Blue Train. Coltrane had promised this one record to Alfred Lion, the head of Blue Note. There was even a small financial advance on it. After that, Coltrane did sign with Prestige Records, but he kept his promise.

1957 was a year of flayings for him. In January he was kicked out of Miles Davis’ band – he should get the hell off heroin, he said. At the end of the year Miles took him back – Coltrane was clean. In the meantime, the saxophonist had played a longer engagement with Thelonious Monk and learned a lot. That flowed into the production of Blue Train in September. It is an album like a springboard – Coltrane is still half on land, half already in the open water. His saxophone playing here gradually liquefies into streaks of sound – the runs are so fast that the individual notes blur. His playing concept moves in higher harmony tones and strives towards the modal solution. The door to the 1960s is wide open. “Coltrane’s first mature statement,” says producer Michael Cuscuna.

Three of the album’s tracks have become jazz standards. You might encounter them at a jam session any time. There’s the charming “Lazy Bird,” which seems to borrow from Tadd Dameron’s “Lady Bird.” Then there’s the ingenious “Moment’s Notice,” which, as the title suggests, came about at the last minute, already in the studio, between doorsteps. And of course the title track, “Blue Train,” all blues, all “Trane” (short for: Coltrane). The theme: a reduced minor riff, insistent, serious, only reluctantly obeying the harmonic changes. Coltrane’s big solo is quite the same: he hardly traces the chords anymore, holds on to his keynote, searches for his lament, actually already wants to play modally. The others are quite different: how they feel their way into the changes, prepare the chord changes and execute them elegantly. Coltrane is one step ahead of them, or several steps. “It’s one of the most beautiful pieces on one of the most beautiful albums Coltrane recorded in the fifties,” Cuscuna says.

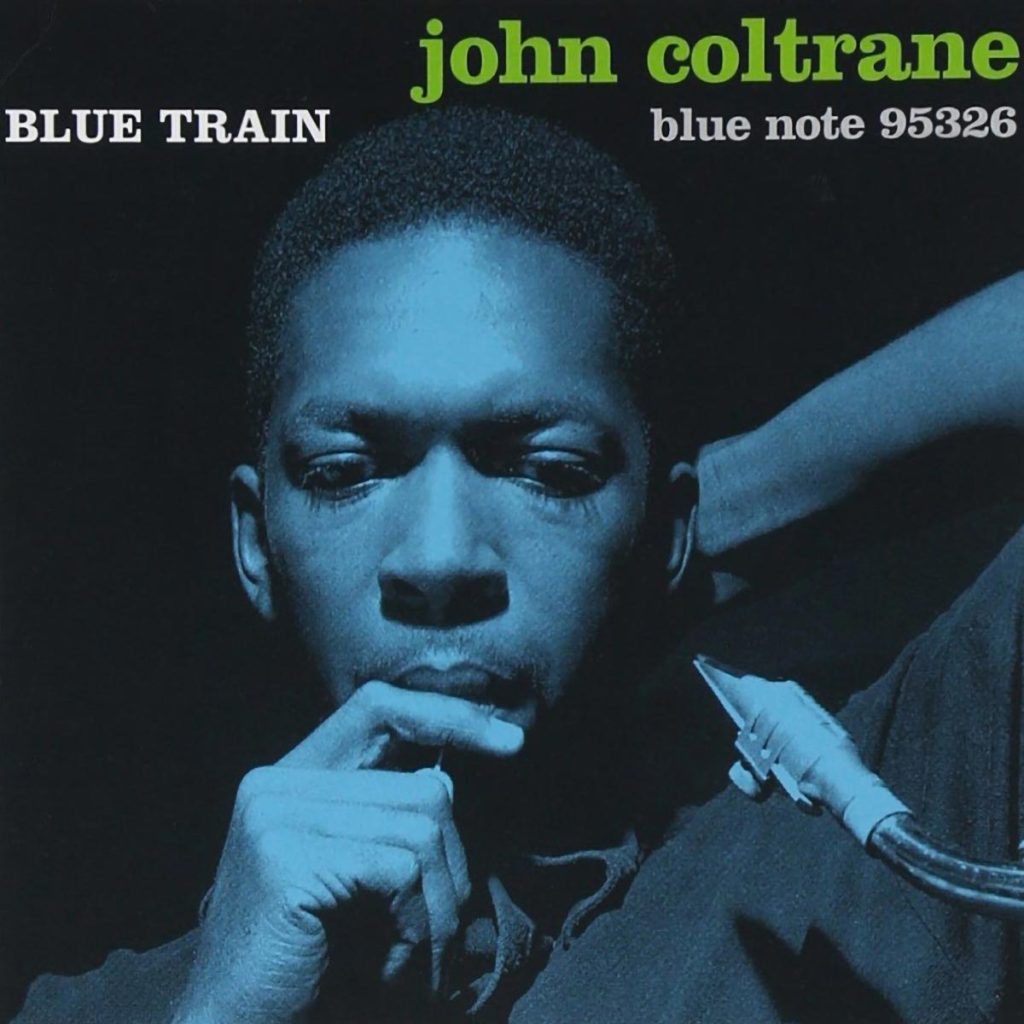

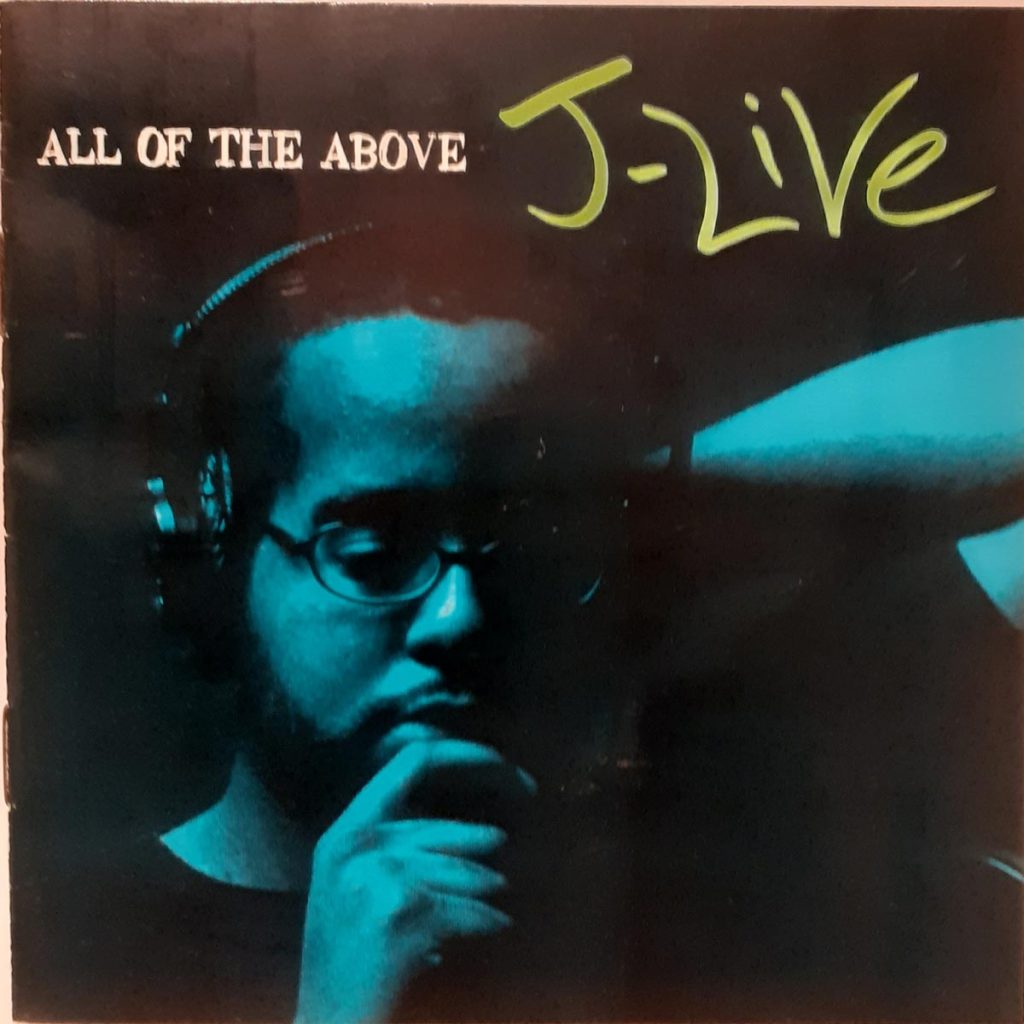

Blue Train’s album cover is also a classic. One of those musician snapshots in the recording studio that Francis Wolff, the skilled photographer and second man at Blue Note, often managed. “With the blue-tinged, tightly cropped image of Coltrane – finger to lip, left arm stretched back, mind immersed in the music – the cover seems as wayward and far from the mainstream as the music itself,” writes Coltrane connoisseur Ashley Kahn. Such classic jazz covers were famously popular models for 1990s hip-hop covers. But with All Of The Above, there seems to be more to it than that. The pose just suits Jean-Jacques Cadet, nicknamed “J-Live.” He too seems to be a serious man (like Coltrane), responsible, pacifist, a thinker. He makes music for a “select audience that cares more about intellect and subtle beats than bombast, bravado, sexism and outrageousness,” according to the All Music website. Also J-Live: definitely opinionated and far from the mainstream. An underground hip-hopper.

He was an English teacher in Brooklyn, he knows about “the kids.” “All they make rhymes about is guns and drugs. But most of them only know these things from music.” J-Live prefers to rap about other topics. All Of The Above was his second album, his “very first second album,” he notes whimsically. The first album the previous year had thoroughly changed his world. He had been around in this world since then, was about to hang up his teaching job. In “MCee,” he celebrates being a rapper: in one passage, he exuberantly strings together only words with M and C. He loves such wordplay – but it’s not the same. He loves such wordplay – but he also has serious things to say. Between the first and second albums: the trauma of 9/11. “Will we even remember the issues and problems we had before that?” J-Live speaks the language of rappers, he wants to reach the kids, but he rhymes unfamiliar things. The magazine called his album “intelligent, educated, confident and socially conscious.” The EmCee, DJ, producer and educator is something like the personified salvation of hip-hop.

John Coltrane: Blue Train (Blue Note BST 81577, published 1958)

J-Live: All Of The Above (Coup d’État CDE 0001, published 2002)

John Coltrane – Blue Train on discogs.com

J-Live – All Of The Above on discogs.com