The alto saxophonist Ernie Henry (1926–1957) played with Monk, Mingus, and Gillespie – and he was on the verge of bridging the gap from bebop to free jazz. However, his life ended far too soon.

He made his first recordings in the 1940s with bebop pioneers like Tadd Dameron, Max Roach, and trumpeters Fats Navarro and Dizzy Gillespie. As an alto saxophonist, Ernie Henry naturally lived in the shadow of the great Charlie Parker at that time. But the youngster had a knack for giving his solos a different twist and avoiding typical Parker phrases as much as possible. In pieces like “The Chase” and “The Squirrel” (both from 1947 with Dameron/Navarro), his playing tended towards a rough cry and adventurous runs through the octaves.

In the early 1950s, Ernie Henry disappeared from the scene for an extended period. It was an open secret that he was battling drug addiction. Heroin use was a sad trend among jazz musicians at the time, and many talents died young from overdoses, including Freddie Webster (1947), Sonny Berman (1947), Dick Twardzik (1955), Carl Perkins (1958), Shadow Wilson (1959), and Sonny Clark (1963). Even Charlie Parker, the leading alto saxophonist of bebop, lost his life in 1955 – heroin and alcohol played a significant role in his demise. When Ernie Henry returned to the scene a year after Parker’s death, his style had visibly matured. He no longer compulsively avoided sounding like his great predecessor but integrated the “Parker tone” into his own phrasing. His sound was aggressive, almost tenor-like. He played virtuoso bop but led his lines across large intervals into remote territories. It’s no wonder that the later avant-gardist Eric Dolphy was a big fan of his.

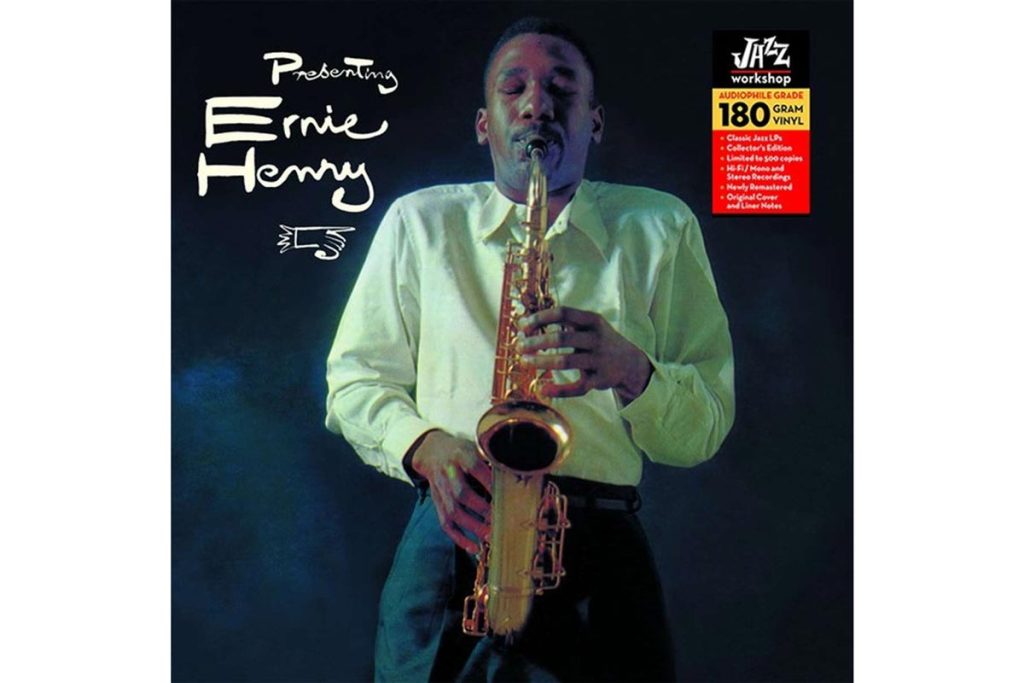

Just a few days before his 30th birthday, Ernie Henry made his debut album: “Presenting Ernie Henry” (Riverside, 1956).

Five of the seven tracks on this quintet album are his own compositions – they lean more towards bebop than hard bop. After the theme, Henry confidently dives into the solos each time as the first player – a virtuoso bopper on the alto sax, but with an urgent “cry” and a modernistic fragmentation of phrasing reminiscent of Jackie McLean. The closing piece, “Cleo’s Chant,” is a genuine blues creeper in the “funky” hard bop style of Horace Silver. The other main soloists on the album are Kenny Dorham (trumpet) and Kenny Drew (piano). In September 1957, Henry made more recordings as a bandleader, but they were only released after his death.

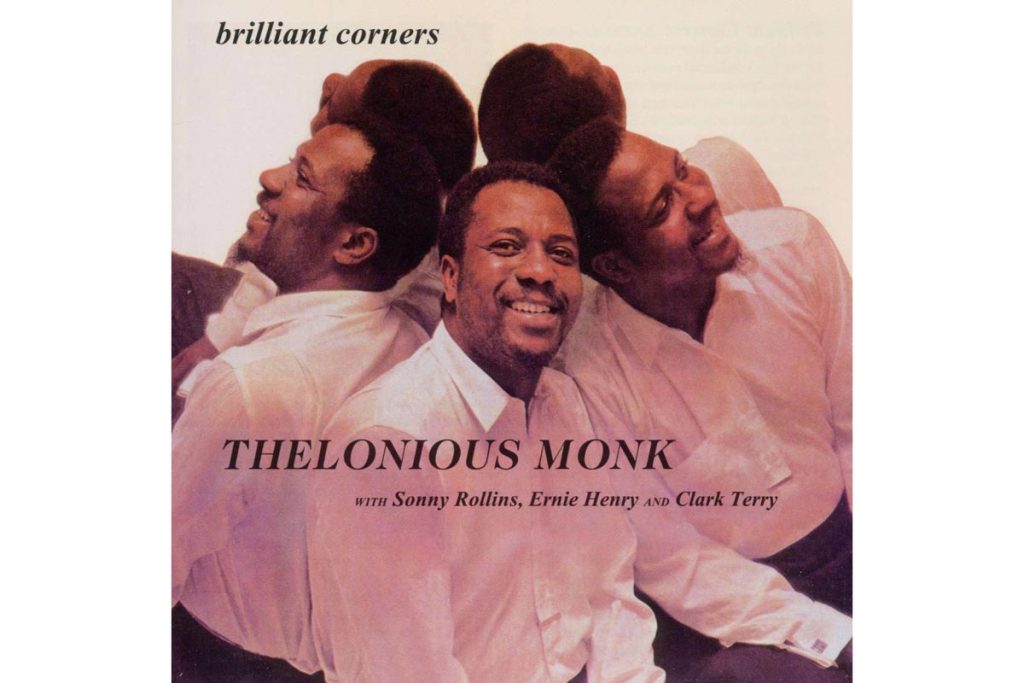

His most famous studio sessions took place in October 1956 with Thelonious Monk. The pianist had booked a distinctive frontline of two saxophones for the album “Brilliant Corners” (Riverside, 1956) (the tenor saxophonist was Sonny Rollins), and he had composed three exciting pieces for it.

In “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are,” a gritty mid-tempo blues, Henry delivers one of his most expressive solos. In the ballad “Pannonica,” where Monk surprisingly employs a celesta, the alto saxophone only plays in the tastefully arranged ensemble part. The second studio date (lasting a full four hours) was entirely dedicated to the title track. “Brilliant Corners” is an highly unusual composition. The band made 25 attempts, but in the end, the producer had to piece the piece together from multiple takes. Ernie Henry was on the verge of a nervous breakdown in the studio. Because Monk’s intricate piano accompaniment irritated him, the bandleader even stopped playing during Henry’s solo (Monk often did the same when playing with Miles Davis). In response, Ernie Henry embarked on adventurous harmonic journeys in his solo. It’s quite possible that Eric Dolphy became a fan of Henry through this very improvisation.

Kenny Dorham, the trumpeter on Henry’s debut album, returned the favor at the end of 1957 by recording the album “2 Horns/2 Rhythm” (Riverside, 1957) together with the saxophonist. The title reveals that it’s a pianoless quartet – and once again, Henry took the opportunity to harmonically loosen his controlled, jagged style. His fantastic playing here points directly toward the freer jazz of the 1960s. The album starts with Dorham’s masterpiece, “Lotus Blossom,” and ends with a down-to-earth blues (“Noose Bloos”) and a pseudo-baroque fugato piece (“Jazz-Classic”). Four weeks after these recordings, Ernie Henry died at the age of 31 from an overdose. There are only a few known photos of him.