As I indicated in my first installment on Fairchild, back in Copper # 75, part of the enjoyment of researching these articles is ending up somewhere completely unexpected.

From Copper Magazine Issue 82

FIDELITY cooperation with Copper magazine.

Read this article also in Copper: Fairchild: Sidebar

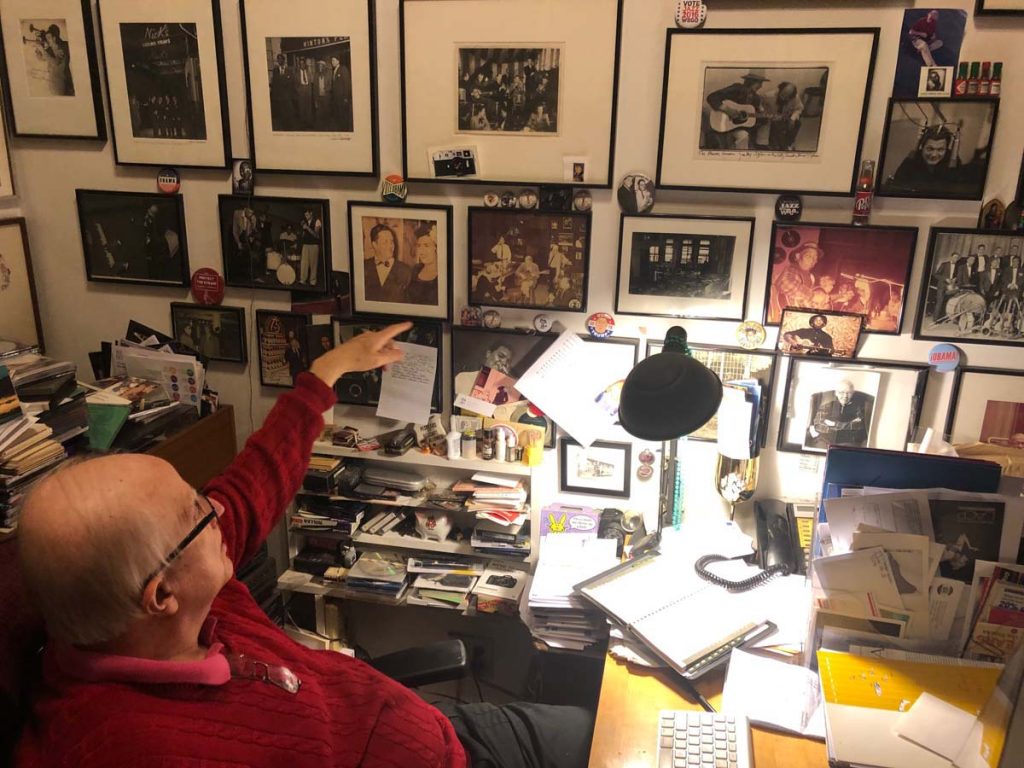

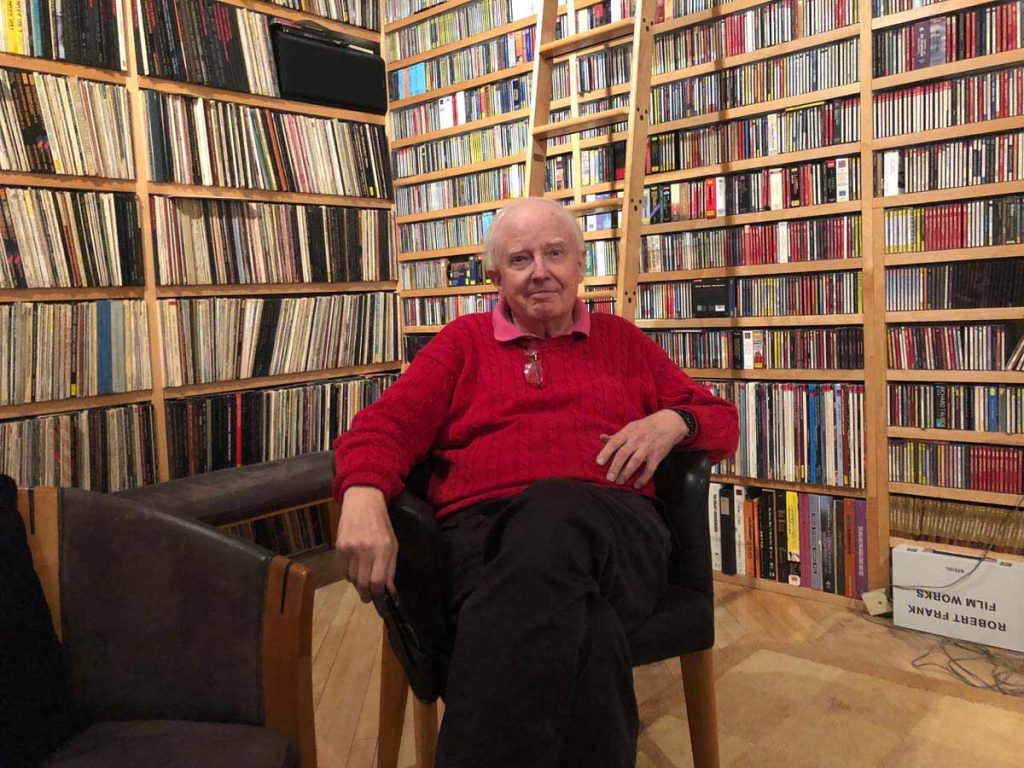

As the series of articles went along, Tom Fine referred me to an old blog by a gentleman named Hank O’Neal, which contained a personal recollection of Sherman Fairchild. I had the pleasure of visiting Hank recently in New York City. My resume is bewildering, but Hank’s is simply mind-boggling. As a young CIA agent stationed in New York, charged with making the acquaintance of leading US industrialists — don’t ask why — O’Neal was led to Sherman Fairchild by a two-fold path. First, someone in Washington needed to know something about the cameras Fairchild’s company Fairchild Camera and Instruments supplied for use in satellites and spy planes, and O’Neal was instructed to go straight to the top: Sherman Fairchild himself. Apparently, such introductions are more easily arranged if one works for The Agency. The second path of introduction to Fairchild? O’Neal was a jazz fan, and had come to know the pianist Marian McPartland. And McPartland was well-acquainted with the music-loving amateur pianist, Sherman Fairchild.

One way or another, in late ‘67 or early ‘68 O’Neal met with Fairchild at his home at 17 E. 65th Street — presently available for a mere $35,000,000, by the way. McPartland had advised Fairchild of Hank’s interest in jazz, and once the agency business was concluded, Fairchild led O’Neal to the living room, past the pair of Steinway grands, and showed him a small room packed with recording gear — most of it made by another of Fairchild’s companies, Fairchild Recording Products. O’Neal was invited to record whomever whenever he liked, and taught himself how to use the compact studio. O’Neal recalls, “I don’t remember the first recording session but I know they started very soon, continued until [Fairchild’s death in] 1971, and there were many of them. Classical, jazz, blues, even a little pop, with artists as diverse as Joe Venuti, Blind Gary Davis, Jane Harvey and a classical duo, Phillips and Renzuli. It was on the job training; I taught myself audio engineering in the small room on 65th Street.”

Keep in mind that all this was happening while Hank was still active as a CIA agent. Within a while, O’Neal, McPartland, and Fairchild founded a record company, which morphed into the Chiaroscuro Records label. Along the way, McPartland departed. As if this weren’t enough to keep a 20-something government agent busy, Fairchild, the pioneering developer of aerial cameras, encouraged O’Neal’s interest in photography. Following a string of illnesses, Fairchild passed away in the Spring of 1971. O’Neal recalls, “A few weeks after his death I was summoned by his lawyers.

They told me that the small record company was Sherman’s last venture with which he was personally involved but his last will predated its formation. They added that because of the complexities of his Estate and because everything would be scrutinized very carefully, all the rules had to be followed. They added they knew Sherman would have wanted me to continue the company and that I should have his share, but because no mention of this was made, I would have to purchase Sherman’s share from the Estate, if I wanted it.

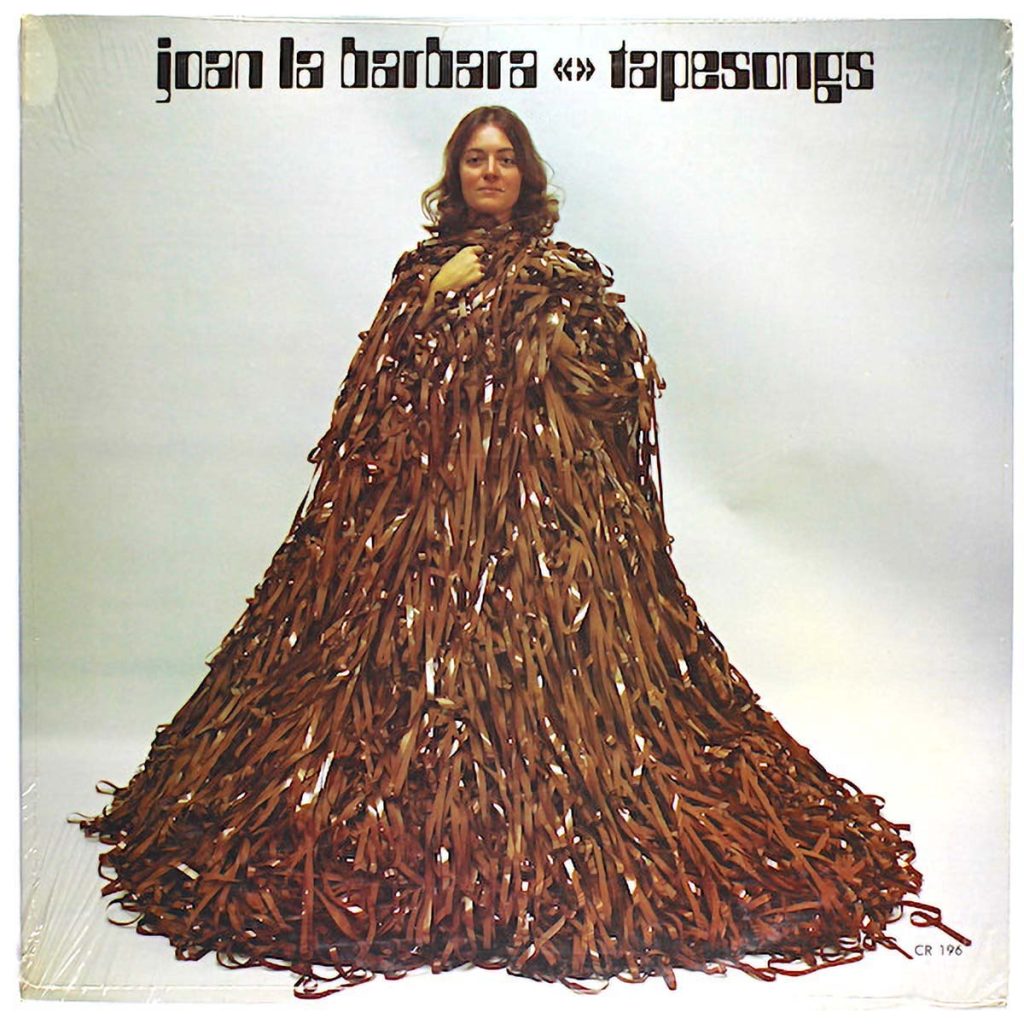

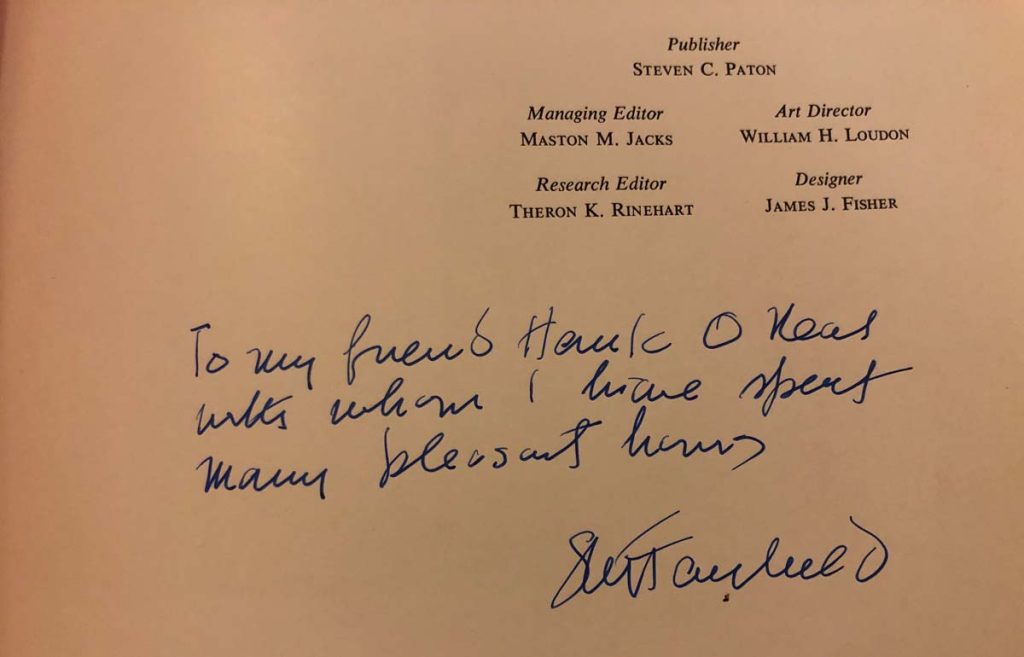

“I asked how much that might be. With a smile, one said, ‘We feel Sherman’s initial investment would be appropriate.’ Sherman, Marian and I had each put up $500 to start the company. I was able to buy the company, all the masters, the bank account and the stock for $500 and this was the beginning of more adventures in music, photography and hundreds of exciting new friends and associates that continue to this day.” Over the last 48 years, Hank has bounced between photography, recording and production (including a short-lived venture with John Hammond, during which time he helped promote Stevie Ray Vaughan), and with his partner Shelley Shier, concert and festival production. He’s also written a number of books; I read his first book, Eddie Condon’s Scrapbook of Jazz, when I was a teenager.

In spite of all his accomplishments, Hank is affable and approachable, still a smalltown Texan in manner and demeanor, and readily invited me to visit after he learned of my interest in Fairchild — whom he still credits with helping him get his start in the recording and music worlds. He’s a skilled story-teller with anecdotes about an astonishing range of folk: his first bookeditor? Jackie Onassis. His mentors in photography? Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, and André Kertész. The Clash, Dr. John, Leonard Bernstein, Willie “The Lion” Smith, Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol? He’s known them all, and dozens more. One book Hank hasn’t written is an autobiography.

Like Sherman Fairchild, he’s a natural subject for a biography. I’ll get to work on it.

Special thanks to Copper Magazine