All of their first hits (“Black Magic Woman”, “Need Your Love so Bad”, “Albatross”, “Man of the World”, “Oh Well”) have been single releases – you couldn’t find them on their regular LPs. The early albums of Fleetwood Mac are largely unknown today.

Originally, british rock music had sprung forth from American Blues. When Willie Dixon and T-Bone Walker toured across Europe, young guitarists like Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and Keith Richards were among the cheering crowd. The year after that, Sonny Boy Williamson even made recordings together with the Animals and the Yardbirds. John Mayall was one of the pioneers of British Bluesrock – his father had owned a great collection of Blues records. On the first record of his band Bluesbreakers, Mayall featured a young Eric Clapton, on the second the even younger Peter Green. While Clapton then went on to found Cream, Green founded Fleetwood Mac. For this purpose, Green wooed away Mayall’s rhythm section (Mick Fleetwood and John “Mac” McVie) and named the project after them. Green also wanted an additional guitarist/singer, just as he was used to during his time with Mayall – to ease the workload as well as for increased density and variety. And whom he found was the slide specialist Jeremy Spencer.

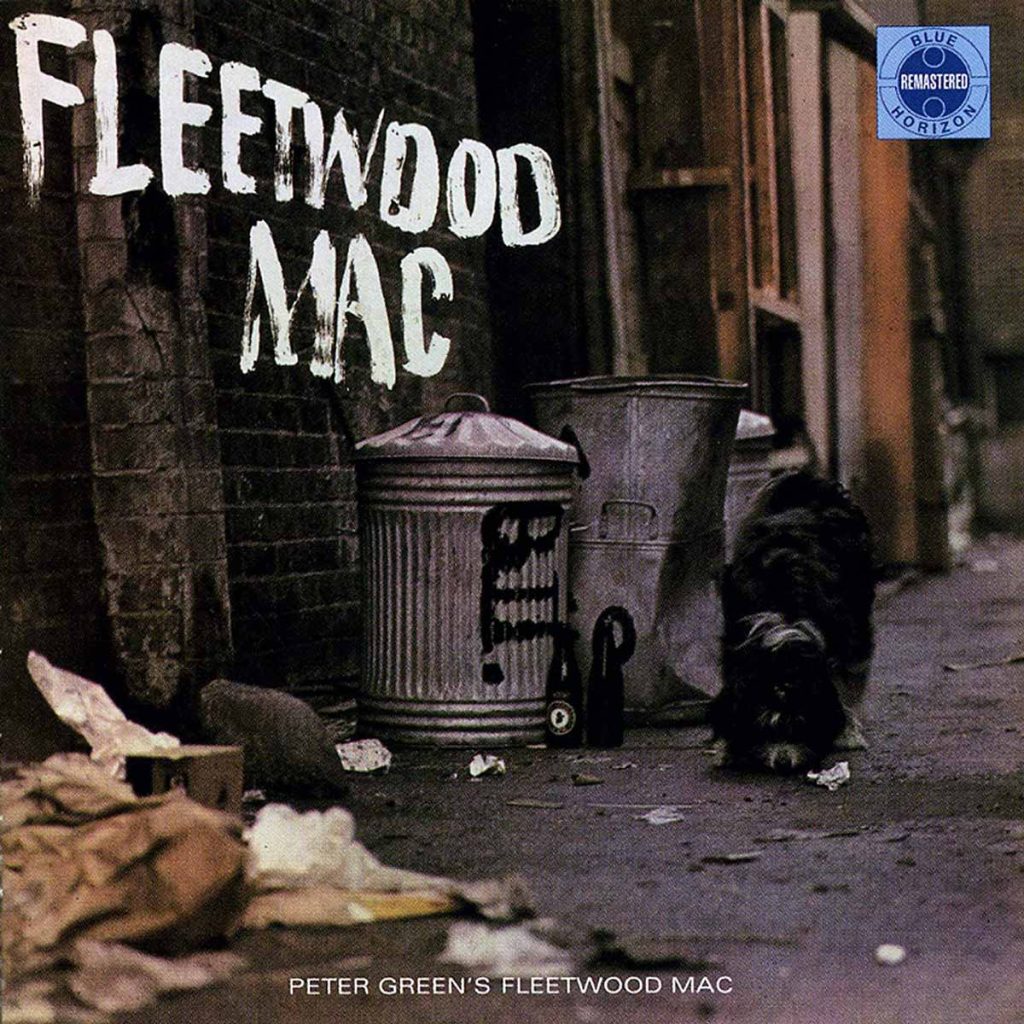

There was a problem, though: Spencer wouldn’t collaborate. On the debut album Fleetwood Mac (Blue Horizon, 1968) you can hear the two-guitar-band only in the songs that Spencer contributed and for which he also recorded the vocals himself (three original songs and two covers, plus a sixth track which he plays solo). Of these, “Shake Your Moneymaker” became most well-known; one of the band’s early singles, though it failed to make the charts. Whenever band leader Green came along with a song, however, Spencer made himself scarce.

In songs like “Long Grey Mare” and “No Place to Go”, Green is in charge of the vocals, the guitar and the bluesharp, all on his own and without any overdubs. These “sparse” Peter Green songs boast a particular emotional character, not quite as direct and harsh as black Blues. Greens “I Loved Another Woman” appears to foreshadow “Albatross” with its spherical guitar sound, while at the same time conjuring “Black Magic Woman” with its latin rhythm. Thanks to its stylistic range, the Fleetwood Mac debut can be counted among the two or three best british bluesrock albums of the 60s.

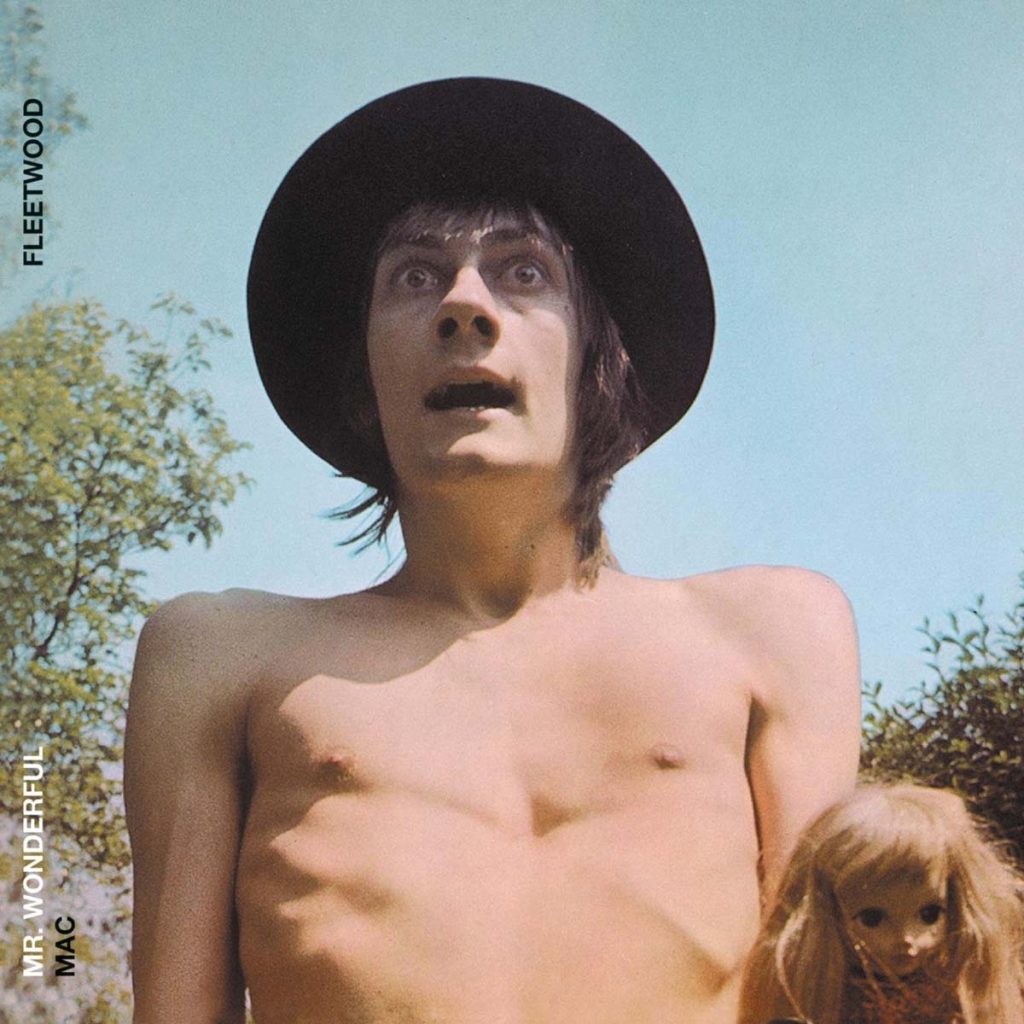

Things didn’t get any better with Jeremy Spencer, though. On the subsequent album Mr. Wonderful (Blue Horizon, 1968) the band comes on harder and louder, but not in a single piece can the two guitarists be heard together anymore – as if there were two versions of the same band.

Spencer rocks away on his blues tracks (three originals, three covers), an instrumental being among those for the first time (“Evenin’ Boogie”). The band leader, meanwhile, tries his hand on six new songs, some of them blues ballads, melancholy and moving: “Love That Burns” or “Trying so Hard” (with Duster Bennett at the blues harp). Peter Green makes the blues form into something visionary and personal: “I don’t sing the blues to keep some old tradition alive” – a jab at Spencer’s penchant for classics by Elmore James. To give the sound more density, many songs – Spencer’s and Green’s alike – feature a wind section (although both prefer different saxophone players). In addition to that, pianist Christine Perfect also plays a part in Green’s songs; as Christine McVie she would later go on to become a permanent band member.

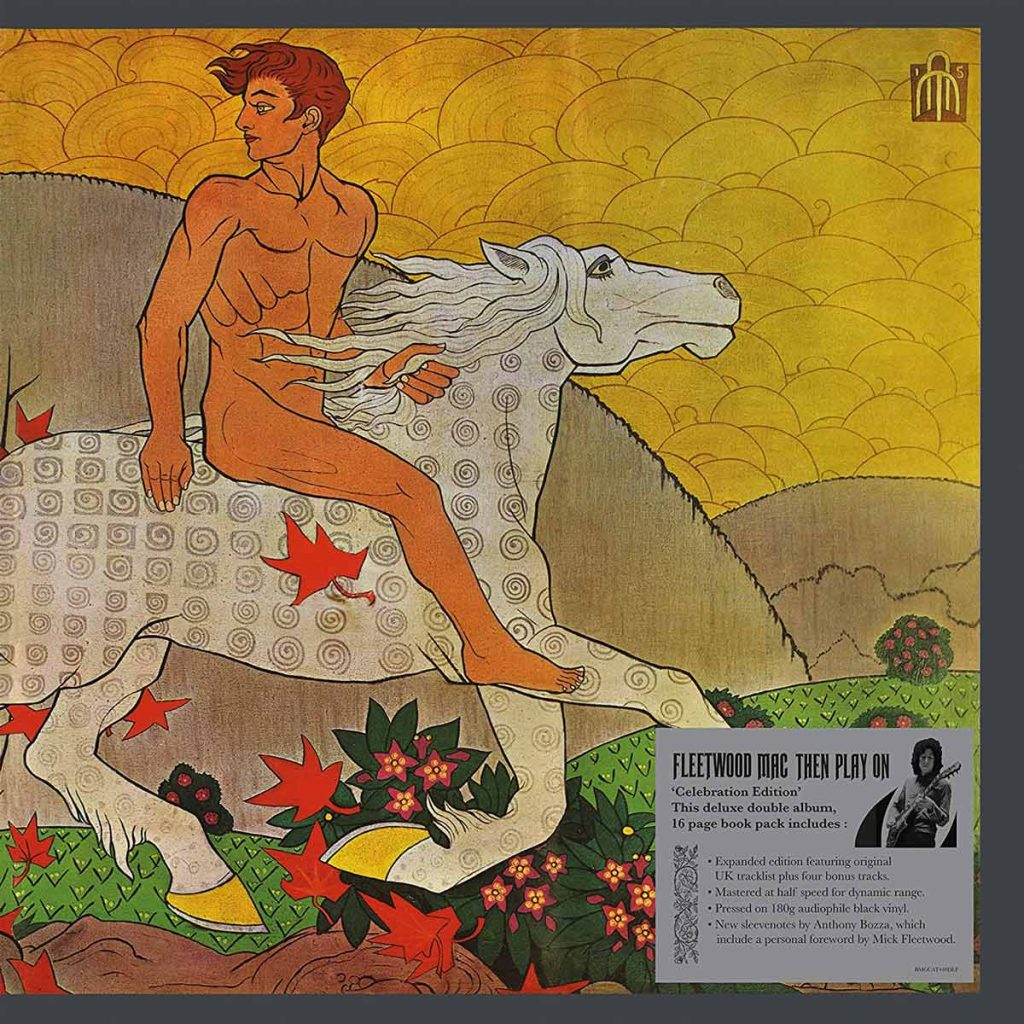

The rift between Spencer and Green grew deeper still. On the third album Then Play On (Reprise, 1969), Spencer (although still a band member) doesn’t feature at all – rather, he publishes his recordings with Fleetwood and McVie as a solo album. Luckily for Green though, he had found himself the guitar partner he always wanted in the still very young Danny Kirwan (this cooperation incidentally brought forth the number-one-hit “Albatross”).

Green grants Kirwan lots of creative leeway – the youngster contributes seven of the 14 tracks (“Coming Your Way” being the most beautiful). For the first time, two gung-ho blues jams are added into the mix, dedicated to a female fan (“Madge”). Kirwans preference for milder moods consistently gels very well with Green’s “visionary” proclivities. The dark kernel behind these had not yet become apparent at that point. Nevertheless, after going through various spiritual and drug-related adventures, Peter Green left his own band in spring 1970. Later he would be diagnosed with schizophrenia. Spencer and Kirwan also left in 1971 and 1972, respectively – and Fleetwood Mac became a different band entirely.