Covering normally refers to songs being performed by other artists, but actual album covers attract their share of impersonators, too. The covered cover: Is it a witty reference, respectful homage or parody? Or is there a deeper meaning behind it?

The man was simply looking for artistic challenges. Jackie McLean, socialized at an early age with alto saxophone, bebop and heroin, jumped on the “New Breed,” the free jazz avant-garde, in the 1960s. He wanted to take up the fresh suggestions of the young, but without cutting the old roots – he wanted to build bridges between old and new. That this was not a commercial calculation is already made clear by the 1965 record text: “There was certainly no financial incentive for him to explore relatively unexplored terrain; the new wave of today is experiencing even bleaker economic weather than its predecessors 20 years ago.” Jump-starting his “second jazz life” was McLean’s sound on alto saxophone – for it has always been screamingly loud, startlingly energetic, unruly and maladjusted. “Sugar-free,” McLean called it himself; it fit the energy of the new, revolting jazz. Because of this sound, Charles Mingus had already brought the saxophonist into his band in the mid-1950s.

McLean was also suitable as a bridge-builder between old and new because he was still relatively young. He had begun his career very early, encouraged by Miles Davis. In fact, the two “neutones” in McLean’s studio band – Charles Tolliver and Herbie Hancock – were only about ten years younger than him. The other two – Cecil McBee and Roy Haynes – were still from McLean’s own generation. For Tolliver, the brass partner on trumpet, It’s Time! marked the recording debut. He supplied three pieces, as did the bandleader – you can hear the difference. Tolliver’s pieces are predominantly modal, his themes freed from the logic of chord progressions and reminiscent of alarming, repeated signal motifs. McLean’s pieces, on the other hand, are still strongly indebted to the hardbop world of the fifties, to funky blues and swinging AABA form.

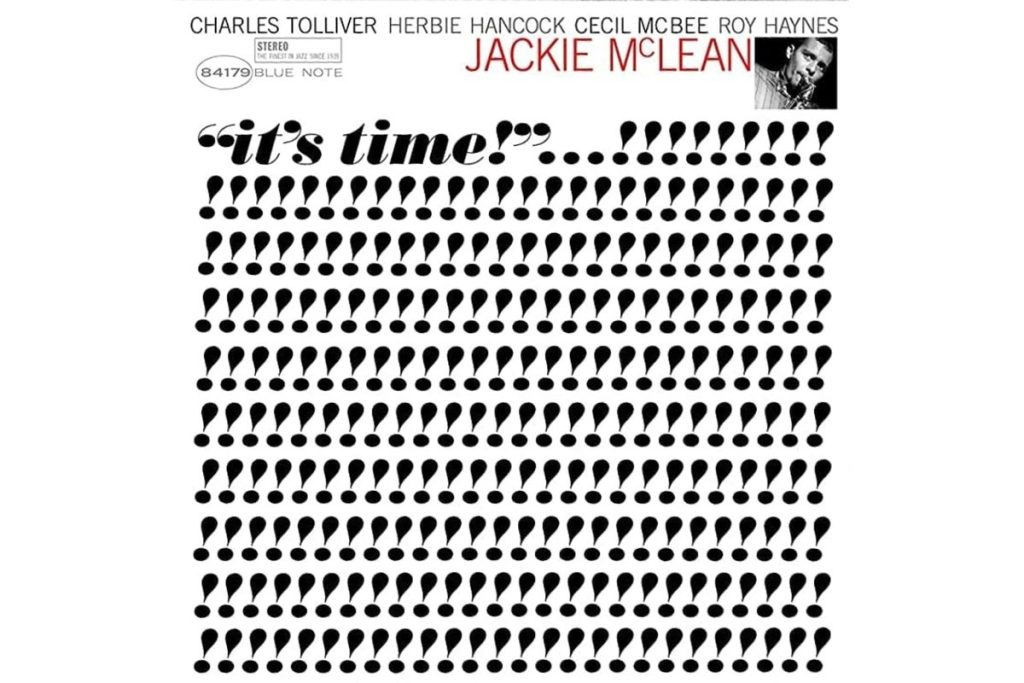

About halfway between old and new is the title track (it’s by McLean). Its name – “It’s Time” – is meant to underscore the urgency of this stylistic bridge-building. Reid Miles, Blue Note’s in-house graphic artist, made the exclamation point added to the album title a graphic cover idea. (Vanishingly small by comparison: McLean’s portrait photo in the upper right.)

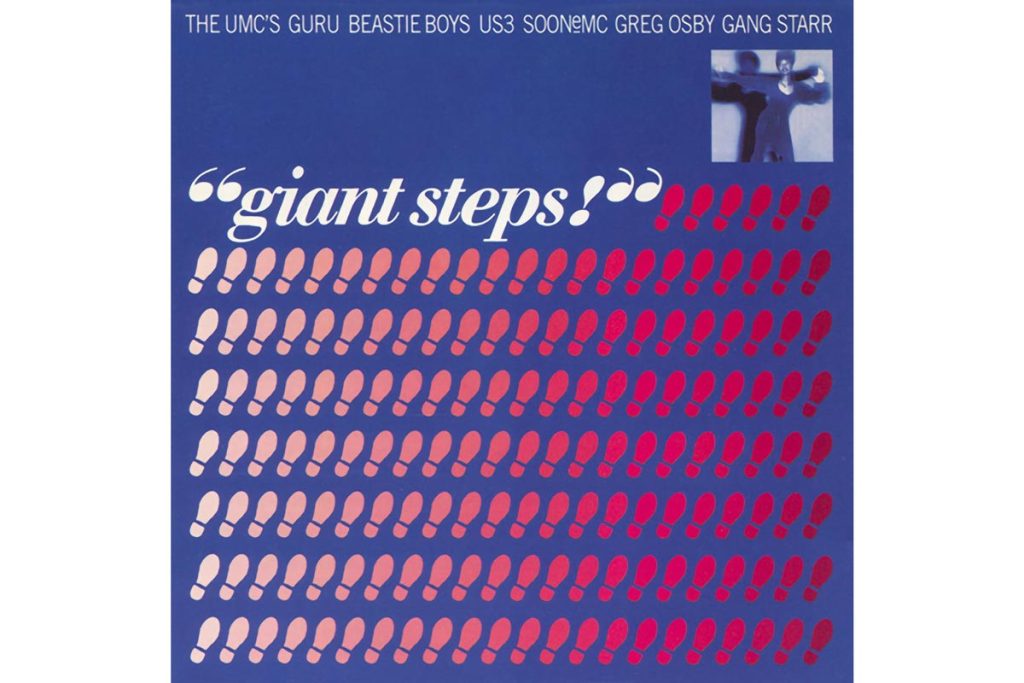

The record sleeve offered an image concept that became iconic and that the British EMI took up again some 30 years later with Giant Steps! – now with small shoe symbols.

John Coltrane’s classic of the same name doesn’t play a role here, though. Rather, it’s about artistic “giant steps” from the past to the present. Giant Steps! is also about a great bridge-building: from the legendary Blue Note world to the world of hip-hop jazz. Artists like US3 and Guru had started to exploit the Blue Note archives for hip-hop around 1990, mainly by way of sound sampling. Some of their tracks consist only of <historic jazz grooves, jazz compings, jazz riffs overlaid with a computer beat and a rap.

The compilation Giant Steps! brings together eleven pieces. Thereby the compilation and the order tell not clumsily about the fashionable connection between Blue Note and Hip-Hop. Almost programmatically, “Cantaloop” is at the beginning, the big US3 sampling hit from 1993 based on Herbie Hancock’s 1964 piece “Cantaloupe Island” (Hancock’s original recording was made just a few weeks before the pianist went into the studio with McLean). Interestingly, however, an instrumental mix of “Cantaloop” was chosen for this album (track 1) – with no human voices at all, but an extensive trumpet solo by Gerard Presencer. This moves the whole thing a bit further towards jazz.

Not only does hiphop jazz look back to the past – the past had already looked into the hiphop future. That’s why this compi also features three tracks from around 1970, when funk-jazz was getting ready to become soulful dance music. “Black Byrd,” a recording by trumpeter Donald Byrd, had been one of the Blue Note label’s biggest hits to that point in 1973 (track 3). Fittingly, Donald Byrd was still quite comfortable in hip-hop jazz 30 years later. There’s a reunion with him in Guru’s “Loungin'” (track 5) – not a sampling, but an original trumpet solo by the then 60-year-old Byrd.

The jumps between eras are actually quite elegantly resolved on this compilation. On the Beastie Boys (track 6), you hear Richard “Groove” Holmes’ Hammond organ prominently sampled – a good segue to organist Reuben Wilson’s soulfunky “Hot Rod” from 1968 (track 7). The organ sound then continues through the next two tracks: We hear Ronnie Foster sampled on US3 (track 8) and then Charles Earland on Lou Donaldson’s “Who’s Making Love?” from 1969 (track 9).

Not to be missed on this bridge album is Gang Starr’s “Jazz Music” (track 10), a rap hymn to the great jazz past: “There was Hawk, the Prez, and Lady Day and Dizzy, Bird and Miles.” Even Charlie Parker’s saxophone was sampled for this track. “Yes, the music / it was born down there / We’re gonna use it / so make the horn sound clear.”

Jackie McLean: It’s Time!

(Blue Note 58285, released 1965)

Various Artists: Giant Steps!

(EMI-Parlophone 827533, released 1993)

Jackie McLean – It’s Time! on discogs