Jazz calls for abstraction – Sabine Kühlich and Laia Genc picked up on the vision that dictated the design of the cover for Dave Brubeck’s Time Out.

“Should some cool-minded Martian come to earth and check on the state of our music, he might play through 10,000 jazz records before he found one that wasn’t in common 4/4 time.” This is how the liner notes started to Time Out, the first jazz album that pretty much let go of using a consistent 4/4 tempo for all its pieces. The album was released at the end of 1959, when the word “out” had a signal effect. “Out” — that was the new jazz avant-garde, a movement that stood on the outside, far from the mainstream and, at times, even far from harmonic rules. For the Dave Brubeck Quartet, in contrast, (almost) only the time was out — the meter, the tempo. Inspired by a tour through various Asian and Middle Eastern countries, including India, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and Turkey, the band began playing jazz in unusual meters. In terms of rhythm, this made Time Out practically a world music album. The opening piece, “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” keeps time in a Turkish aksak rhythm (2-2-2-3), “Three to Get Ready” alternates between 4/4 and 3/4 tempos, “Pick Up Sticks” keeps a 6/4 tempo, and “Take Five” is in 5/4. In 1959, this album concept was considered a bold, unprecedented experiment.

And it gave the people at Dave Brubeck’s record company, Columbia, an uneasy feeling. They insisted the quartet first record a conventional album with very American standards that would be released at almost the same time as Time Out. And they had no idea which piece from Time Out they should promote as a single — none seemed appropriate as a dance song. The decision was made at the top level: Goddard Lieberson, president of Columbia, chose “Take Five,” the only song on the album not composed by pianist Brubeck himself, but rather by saxophonist Paul Desmond who had been inspired by the beeping sounds of a gaming machine where he had lost a lot of money. He claimed to have written “Take Five” as payback for the loss inflicted by the machine. After coming up with two short motifs in 5/4 tempo, he made them into parts A and B of his theme. Joe Morello, the quartet’s star drummer, really shone on the piece with his drum solo. Brubeck also made a few suggestions and proposed the song’s title: “Take Five.”

The album unnerved not only the record label, but the critics, too. One compared “Take Five’s” 5/4 tempo with Chinese water torture. And crazy enough, precisely this song developed into the greatest hit in modern jazz at the time. To achieve success, it took “Take Five” two whole years! But it climbed into the American Billboard charts, making Time Out one of the hottest selling jazz albums of all time. The piece “Take Five” has been played by numerous musicians, has developed into one of the most well-known jazz standards, and has even taken over elevator playlists. For Time Further Out, the follow-up album to Time Out, Brubeck wrote two new pieces in 5/4 tempo; throughout his lifetime, he composed dozens even.

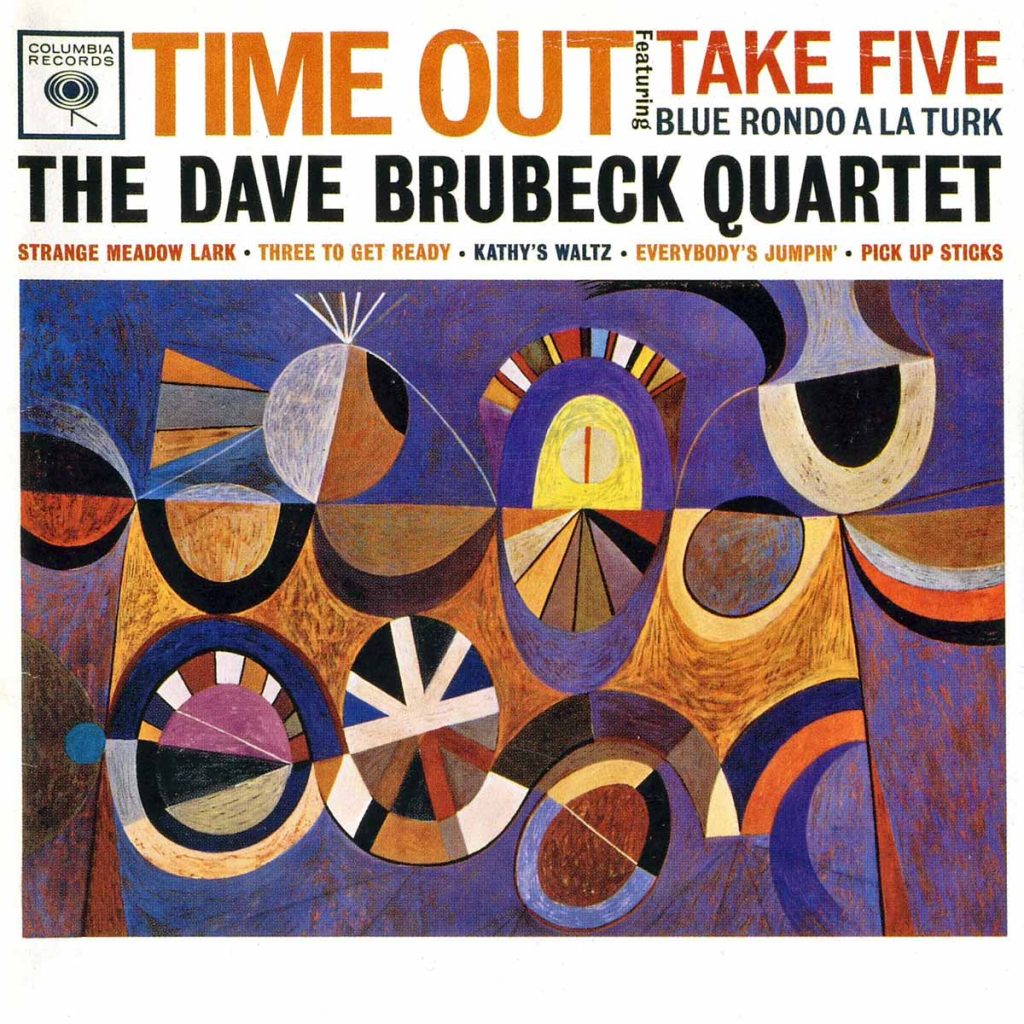

Because the album Time Out was so unusual, it needed an unusual cover. Sadamitsu Neil Fujita (1921–2010), the head of the art department at Columbia Records at the time, was convinced: “Jazz calls for abstraction, for modern painters.” Fujita liked artists such as Paul Klee, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso and occasionally acquired licenses to use modern works of art on album covers. But for Time Out, the boss took matters into his own hands: The abstract image on the front is a genuine Fujita. That same year, he had done something similar for the Charles Mingus album Ah Um.

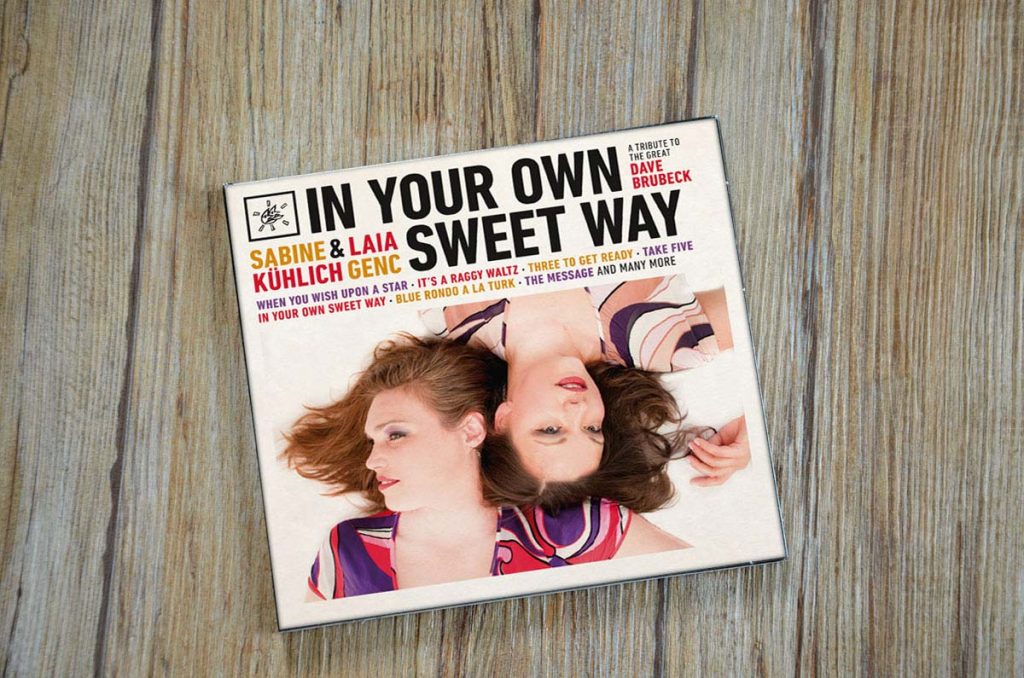

At the time, he couldn’t know that, 55 years later, his image for Time Out would inspire two young jazz musicians to be photographed in colorful, abstract-patterned clothing. The album In Your Own Sweet Way from Sabine Kühlich and Laia Genc does, of course, pay homage to Dave Brubeck. Four songs from Time Out reappear here, plus another eight Brubeck compositions from albums such as Dave Digs Disney, Time Further Out, Brubeck Time, Brubeck Plays Brubeck, and Jazz Impressions of Japan. For Kühlich, Brubeck was an important musical influence, a real eye- and ear-opener; Genc is particularly fond of his ballad, “In Your Own Sweet Way”. Both musicians translate Brubeck’s music into nimble, playful duets perfectly at home in a cozy, artistic space outside of the everyday jazz sound and far removed from the historical context of cool jazz and metric avant-garde. Kühlich seems to slip into the role of Paul Desmond as she plays the alto saxophone with the lightness usually reserved for a flute. On piano, Genc rivals Brubeck’s forced block chords. Kühlich also puts her remarkable talent as a jazz singer on display. The texts for the Brubeck songs stem from Iola Brubeck (Dave Brubeck’s wife), Kurt Elling, Al Jarreau, and Kühlich herself, among others.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet | Time Out (CBS 460611 1)

Sabine Kühlich and Laia Genc | In Your Own Sweet Way (Double Moon Records DMCHR 71164)