Covering normally refers to songs being performed by other artists, but actual album covers attract their share of impersonators, too. The covered cover: Is it a witty reference, respectful homage or parody? Or is there a deeper meaning behind it?

The quartet of saxophonist Charles Lloyd was one of the most successful bands in jazz in 1967 – not least because the formation managed to leap over the border to pop and even get a young rock audience excited. Rather than dark suits, the musicians wore gaudy shirts on stage; they were considered “the first psychedelic jazz band,” the first hippies in jazz. In their music they merged soul rhythms that rocked with Coltrane-like jazz ecstasies. Keith Jarrett was the name of the young pianist of this quartet – he was a border crosser from the beginning. Jarrett’s piano playing contained some of the white folk rock and some of the black soul. He was an extraordinary virtuoso, but at the same time open to harmonic adventure and wild free jazz. An unusual combination in a pianist.

May 1967 also saw Keith Jarrett’s debut album under his own name: Life Between The Exit Signs. A piano trio, right – but what a trio! On bass: Charlie Haden, made famous in the quartet of free-jazz father Ornette Coleman. On drums: Paul Motian, longtime accompanist of the subtle Bill Evans. Haden and Motian – both considerably older than Jarrett – were already minor legends at the time, but they seemed difficult to reconcile: the “free” organ point bassist and the “delicate” drum wizard. Ornette Coleman’s fans weren’t typically fans of Bill Evans – and vice versa. But Keith Jarrett, who had just turned 22, evidently knew exactly what he was doing. Harmonic liberation and pianistic delicacy were no contradictions to him. “Never before had I played with a pianist who now and then simply left the chord structure and played freely,” Charlie Haden noted. Today, that trio is considered classic. They would stay together for ten years.

Jarrett went on to become a world star. He rose to become the figurehead of the ECM label, heck, of jazz in its entirety. His Cologne Concert conquered the bourgeois living rooms, and the pianist kept filling the largest concert halls for decades. In 1967, all of this was still in the future. But the debut album already gave us a taste of the coming Keith Jarrett: the countryesque piano phrases, the brash rhythm, the ecstatic explosiveness, the ingenious melodicism often reminiscent of Ornette. The piano trio instrumentation was to remain Jarrett’s “aesthetic sound ideal” for the rest of his life (according to Wolfgang Sandner). Even here, you can already hear Jarrett softly sing along as he models his visionary, fantastic runs. Jazz journalist Mike Collins on the opener, “Lisbon Stomp”: “Today, the piece appears to be the quintessential Jarrett. Even the sound of the piano is already unmistakably his sound. It’s as if he appeared on the scene, already fully formed and with an unmistakable tone right from the very beginning of his long career.”

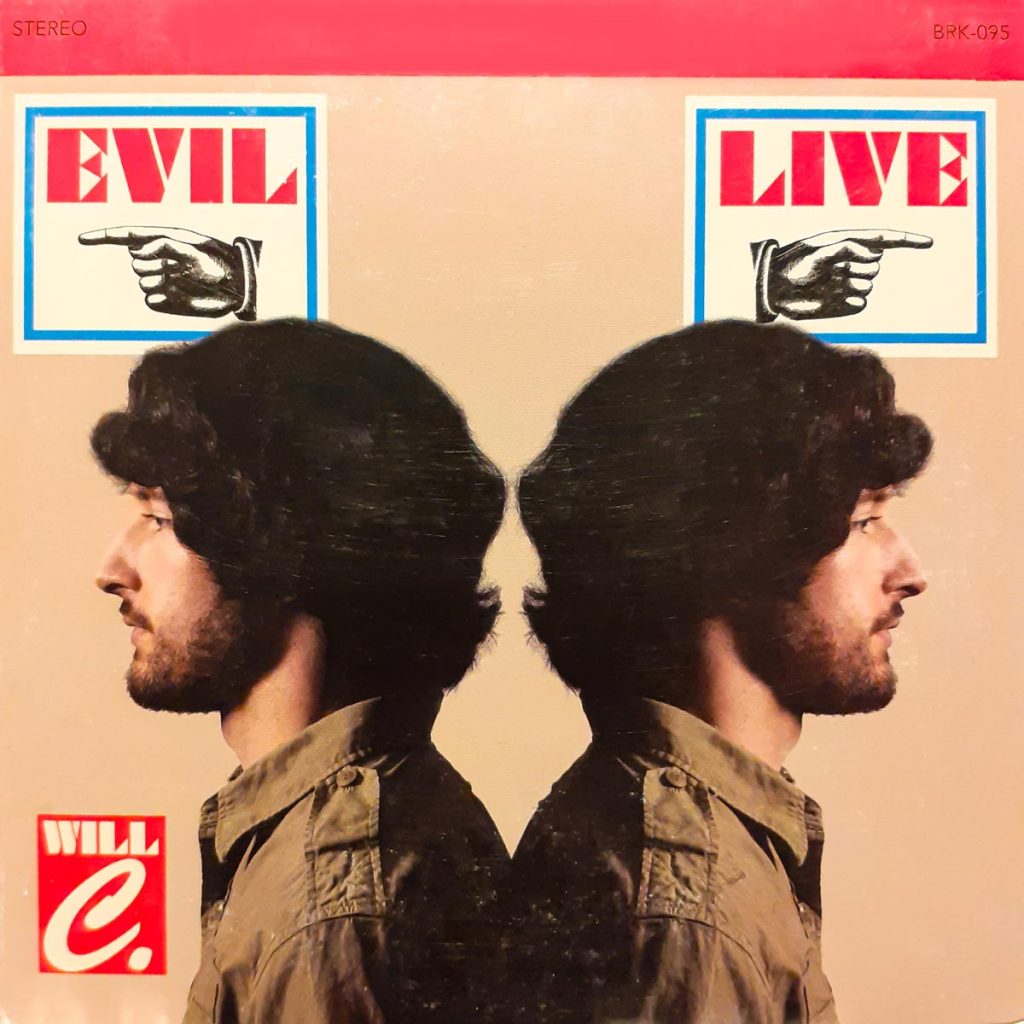

Life Between The Exit Signs – what is the album title supposed to tell us? Does it mean the span of life between birth and death? The artistic creation embedded between past and future? Jarrett’s little commentary on the album sleeve suggests otherwise: He speaks of exits that become audible in the music. Perhaps: liberation and inwardness, ecstasy and lyricism, Ornette Coleman and Bill Evans. The psychedelically Janus-faced Keith Jarrett on the album cover seems to reflect this duality in his music. Loring Eutemey (that was his real name!), glorious chief designer at the Atlantic record company, created the album cover. Trevor Gendron, called “Karma”, adapted it more than 40 years later (2009) for the album Evil In The Mirror (the official title) by hiphop artist Will C. (That “Evil”, palindromically mirrored, results in “Live”, is something Miles Davis also knew already: His album Live-Evil was created in 1970).

Will C. (full name: William Curley) is a special kind of hiphopper. This is already revealed by the loving details of the album cover: the black cap, which makes a resemblance to Jarrett’s hair mat, or the imitated logo at the bottom left. Incidentally, the back cover also bears a resemblance of the original. Curley’s little accompanying text reads serious and thoughtful and is a far cry from being hip-hop jargon. He explains his Janus face in terms of the duality of our personalities: egotism vs. empathy. He’s unsure of the direction his life will take, he writes, but ironically, he can admire the prospect that’s presented to him right now. All the lyrics to his 14 rap songs are printed in the CD booklet, which, incidentally, is as artistically designed as it is nobly finished. It’s quite evident that he is taking his music aesthetically seriously. The sound carpets that Will C. has assembled from music samples for his raps are well worth listening to. Tasteful and atmospheric.

In a way, it was already foreseeable at that point that rap would not remain his musical goal. Will C. is above all an inspired sound designer on the computer. A few years ago, his electronic reworking of Beach Boys classics, with which he wanted to give them a “new, unexpected aesthetic,” attracted attention. Even the Boston Globe was enthusiastic: “Ambitious and brilliant”.

Keith Jarrett: Life Between The Exit Signs (Vortex/Atlantic)

Will C.: Exit In The Mirror (Brick Records)

Keith Jarrett – Life Between The Exit Signs on discogs

Will C. – Evil in the Mirror on Bandcamp