Jazz is like a dense forest where it s easy to overlook something important. Hans Jürgen Schaal points out a few highlights of jazz history we may have missed.

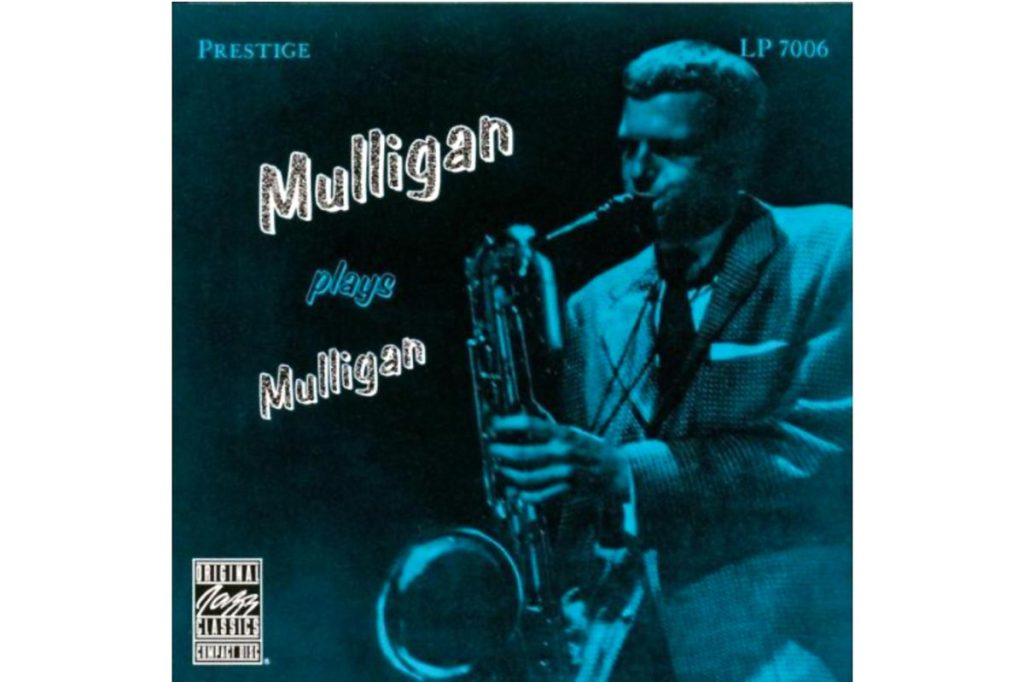

The record Mulligan plays Mulligan really shouldn’t exist. In the official history of jazz it plays practically no role, even Gerry Mulligan usually skipped it in interviews. The recordings were made on August 27, 1951, in Hackensack, New Jersey. The young Rudy Van Gelder was the sound engineer, at a time when no one had ever heard his name at the Blue Note label. He had set up a small control room next to his parents’ living room, everything was still makeshift and experimental. The musicians who came to visit that day were also still experimenting. That summer, they sometimes rehearsed on the lakefront in Central Park – until the police drove them away.

Until then, saxophonist Gerry Mulligan had mainly played in big bands, even writing a few arrangements. His most important achievement was his participation in Miles Davis’ Capitol Orchestra (1949/50) – there Mulligan formed the innermost core together with Miles Davis and Gil Evans. He wrote three pieces for Miles’ nonet and arranged three others. But only a few of these recordings were released promptly (on 78 discs). Not until 1957 would eleven of the twelve pieces appear on an LP, which was then appropriately titled Birth Of The Cool.

In 1951, the historical significance of Capitol Orchestra was not yet apparent. But Mulligan continued to pursue the ideas he had developed with Miles Davis and Gil Evans: the relaxed tempos, the mellow six-wind sound, the melodic lines – things that would constitute the soul of cool jazz. At Rudy Van Gelder’s, Mulligan showed up with his own nonet, augmented to the tentet by Gail Madden, Mulligan’s girlfriend at the time, on maracas. The musicians had prepared six pieces – typical Mulligan themes that mostly saunter along in a relaxed manner, inviting the listener to hum along or whistle along, catchy melodies, elaborated in counterpoint. At the center is a sonorous wood sound: a tenor saxophone and two baritone saxophones. The two baritones open the first piece (“Funhouse”) without rhythm accompaniment – already that was quite unheard of.

The six pieces appeared on a 10-inch disc at the time, a brand new recording format. Mulligan plays Mulligan was Gerry Mulligan’s debut album: for the first time, the then 24-year-old was heard improvising extensively on the baritone sax, in that unaffected, shirt-sleeved manner he had copied from Lester Young: light, fluid lines, every phrase a melody. The second main soloist, Allen Eager on tenor sax, is in the form of his life on these recordings. When the record was later reissued as a 12-inch, they packed a blues jam (“Mulligan, Too”) from the same day on the B-side: just Mulligan, Eager and the rhythm section. A 17-minute improvisation without a theme – a pioneering act.

A few months after these recordings, Mulligan moved to California. There he formed his first official band, the quartet with Chet Baker, which became the launching pad for West Coast jazz. But for all intents and purposes, West Coast jazz began in Hackensack on August 27, 1951. The six-wind format then became a standard in California’s cool scene.

Mulligan plays Mulligan on discogs.com