In the 1980s, the ole fifties were far enough in the past to become “chic” again. Gentlemen’s hats, shoulder pads, kidney-shaped tables, patent leather shoes and rock’n’roll – they celebrated a strange, post-modern comeback in the 1980s.

Jazz was also affected. Suddenly the old jazz sounds were back in fashion, so-called “rare grooves” were playing in discotheques, and the album sleeves from around 1957 were inspiring young designers by the dozen. In 1986, journalist Steve Lake wrote: “English glossy magazines pounced on jazz as if it were a gift from God. A ‘look’ was cultivated. It required all kinds of accessories. Black turtlenecks and duffle coats, baggy pants and maybe a Blue Note album under your arm.” In the jazz world, the old hard bop, that earthy, groovy, gospel jazz of the late 1950s, was suddenly present again. No one had missed it in the 1970s: hard bop was still regarded – if it was remembered at all – as an outdated fashion, conventional and uniform, a mass-produced commodity from the past. But then it came back, the proverbial Blue Note sound, and seemed to be filled with new meaning. Even Blue Note itself, the half-forgotten label, was re-established in 1985.

Surprisingly, John Zorn, New York’s notorious avant-gardist, known for his noisy and shrill musical excesses, was right in the middle of the hard bop revival. This John Zorn of all people reactivated the Hammond organist “Big” John Patton, a legendary Blue Note veteran, and made several new albums with him. This John Zorn, of all people, also took on the saxophone job in the so-called Sonny Clark Memorial Quartet, which recorded seven pieces by the decades-long underrated Fifties pianist Sonny Clark. This John Zorn of all people developed a real “obsession with the masterpieces of hard bop” in the 1980s, as journalist Peter Watrous wrote. Zorn did not see the groovy pieces from Blue Note’s golden era as uniform mass-produced goods. Rather, he valued them as small, concise compositional jewels. He helped open a treasure trove that keeps on giving to this very day.

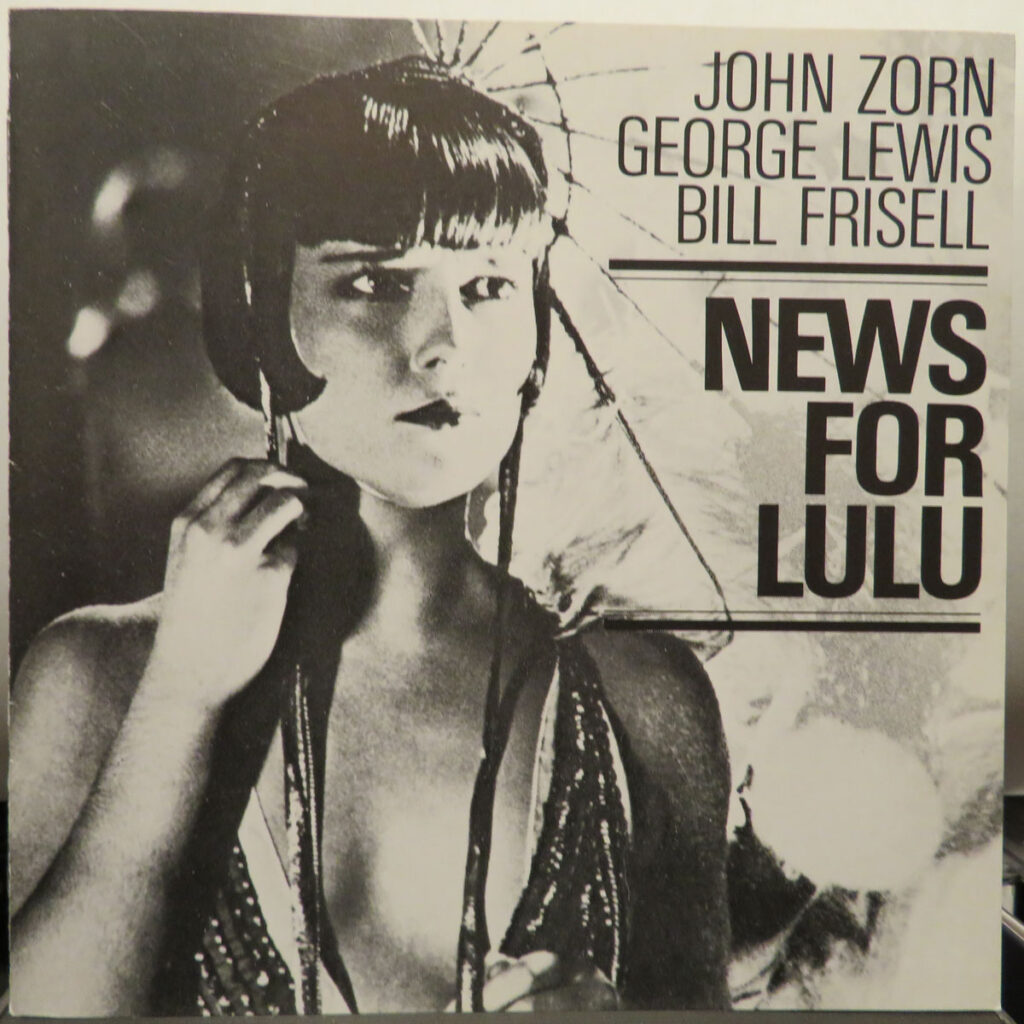

Zorn’s strongest arguments for the compositional aesthetics of hard bop were delivered on News For Lulu.

The album presents 16 selected compositions by four hard bop greats: trumpeter Kenny Dorham, saxophonist Hank Mobley and pianists Sonny Clark and Freddie Redd. These compositions were largely forgotten at the end of the 1980s and the original records had been out of print for 20 years. Zorn presents these pieces as if they were completely new and unused. He does not play them in a hard bop sound, not with a grooving rhythm section, but in a risky trio constellation of alto saxophone (John Zorn), trombone (George Lewis) and electric guitar (Bill Frisell). Swinging, the three improvise as a team, sometimes lean and cool like the Jimmy Giuffre Trio with a similar line-up, then again loud and garish like the free jazz master Ornette Coleman, but always in compact portions of three to four minutes, following clear lines, striving for a “precise shaping and refinement” (Jürg Laederach). This is virtuoso chamber jazz post free. The timeless essence of the faded hard bop.