Soul sings Country, Country sings Soul – For his employer Ace Records, he first compiled three CDs with soul-interpreted country songs. When plans were made for a fourth CD, Tony Rounce decided to turn the stylistic direction around.

Ever since the 1950s, you could find small radio stations all over the US that have been satisfying the particular cultural needs of their listeners. “Because of racial segregation, radio DJs in the South only rarely played blues or jazz,” Rounce discovered when carrying out research for an oldie CD. “Most soul singers of the ’60s had heard plenty of country music on the radio as children.”

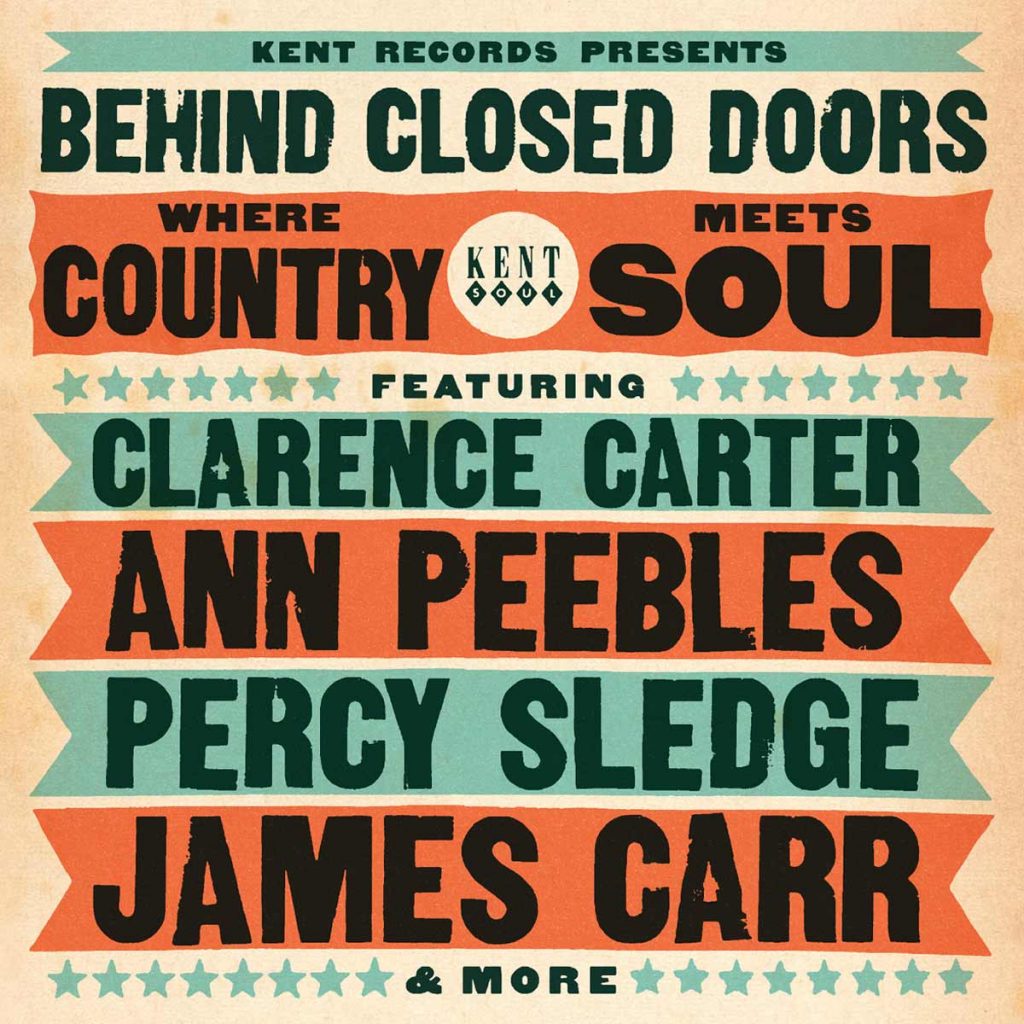

The Behind Closed Doors — Where Country Meets Soul album compiled by Tony Rounce appeared in 2012. The CD begins with “Grand Tour” by Aaron Neville. The sentimental soul singer from New Orleans had interpreted this song with such schmaltz in 1993 that his version was even popular among country radio station DJs. It had been written by Nashville star George Jones, who Frank Sinatra once said was the second best singer in the US (Frankie Boy never revealed who the best was).

Following the soft subcutaneous ripples from this earthquake, the album steps it up a notch. Solomon Burke, celebrated as the King of Rock ’n’ Soul, shows the always gentlemanly and well-behaved Jim Reeves how his hit, “He’ll Have to Go,” should have actually sounded. By the 10th track, the CD listener has finally reached the point of no longer knowing what is black and what is white; what is worldly music and what is spiritual music. Gospel preacher Al Green (“I don’t like it when people come into my church just because they like my records”) from Memphis, Tennessee, sang “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” in 1973. Hank Williams had used it to show white rock ’n’ roll rebels and African-American rhythm ’n’ blues musicians a possible form of expression way back in 1949. Later, with “Life Turned Her That Way” from James Carr, the Hammond organ begins to simmer and boil a little more. The e-bass pushes forward more powerfully from track to track. By the CD’s 15th song, “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad” by Cookie Jackson, it even sounds funk.; Tamla Motown announces itself as a future market leader. And then when Arthur Alexander yearns for those “cotton fields and home” in “Detroit City,” it sounds more credible than the commercially more successful version by country singer Bobby Bare.

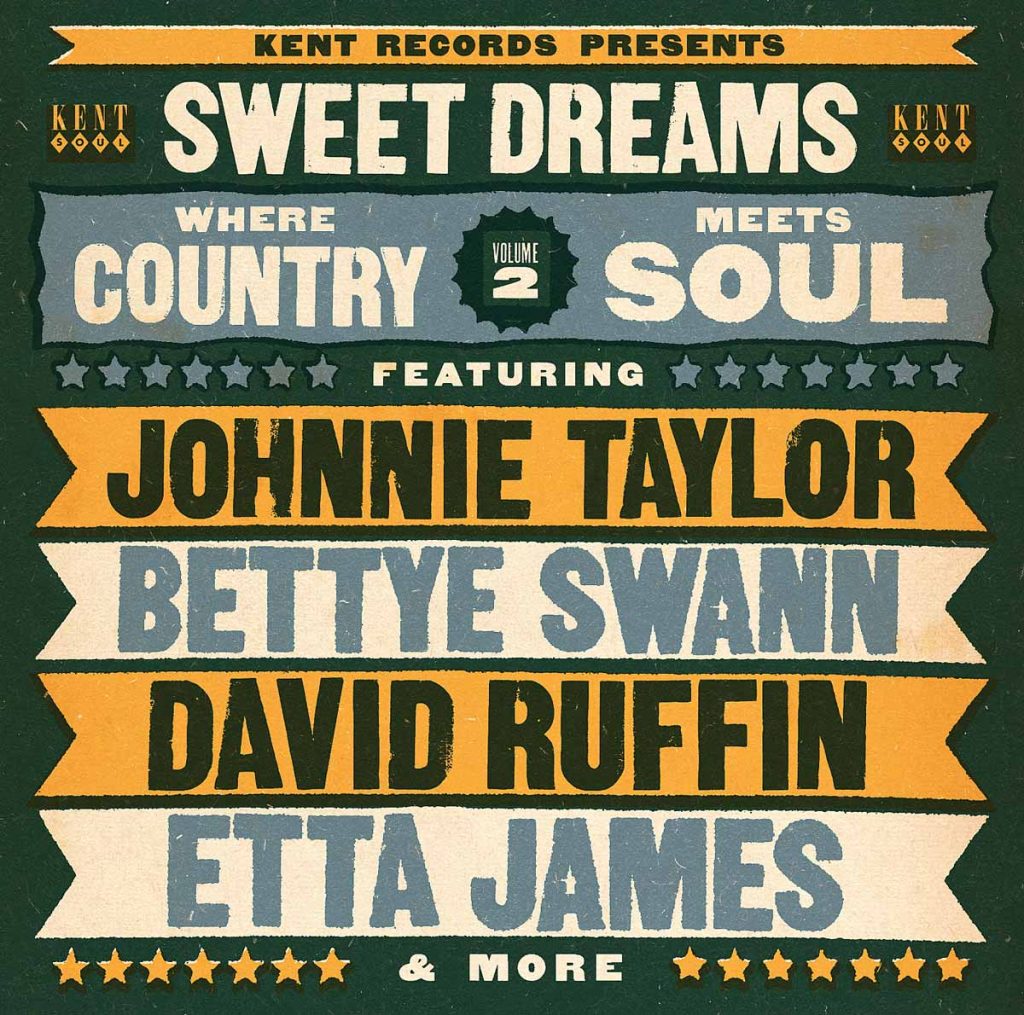

For all CD listeners who want to compare the respective country original with the soul version heard here, Rounce has listed the original record release of each individual song in the booklet. “But I haven’t presented the tracks in a strictly chronological order on the CD,” the compiler emphasizes. “The recording dates of the individual songs were not a priority for me.” His compilation follows a stylistic logic instead. Roger Armstrong, Managing Director of Ace Records, confirms: “This compilation is a typical Ace CD. It’s really good ear candy and perfect for a dance party.” The success of Behind Closed Doors encouraged Armstrong to have his employees research further in this direction. Ace Records released the follow-up album Sweet Dreams – Where Country Meets Soul Vol. 2 in 2013. This is where roots and history, style elements and mutual influences of soul and country music blur and intermingle conclusively. “Help Me Make It Through the Night” and “Sunday Morning Coming Down” sound as if the outlaw bard Kris Kristofferson hadn’t written them for white country buddies, but rather for more powerful soul voices.

On volume 2, Otis Redding has his big appearance with “Tennessee Waltz.” The female trio Sweet Inspirations, on the other hand, gave it a somewhat less conspicuous treatment with the original white repertoire back in 1969. With “But You Know I Love You,” the three Elvis companions turned themselves toward Las Vegas and away from black Memphis. With its sophisticated, jazzy Philly sound, the CD’s finale, “Forever’s a Long, Long Time,” taps into the flourishing disco scene as a new realm for black soul artists.

In 2014, Rounce titled his third intercultural project (an homage to the hillbilly Shakespeare Hank Williams) Cold Cold Heart: Where Country Meets Soul Vol. 3. With a ferociously fiery heart, Johnny Adams apparently only delivered a misinterpretation of the title song in 1963; in reality, the falsetto soul singer actually rescued the 1951 hit from obscurity with his version. Taken as a whole, volume 3 documents a perfectly successful gene manipulation — a stylistic pinpointing of birthplaces such as Memphis, Nashville, Detroit or other such music production sites is no longer possible. The originals of some songs on the CD even reach back to the 1930s. In any case, this CD has to be recommended to jazz and blues-guitar lovers as well.

In 2015, Rounce turned the tables. For him, putting together the Ace album Out of Left Field — Where Soul Meets Country was about demonstrating the influence that the soul bards had exercised on their white country buddies. The bad news first: “Dock Of The Bay,” the song that gave Otis Redding his greatest sales success posthumously in 1968, was covered in 1982 by the venerable country veterans Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson. On this recording we can hear how the two western legends approached the song with far too much regard for the original artiste, probably wanting to appear as cool as possible. It also sounds perfectly “fabric softened” for playing on every country music radio station aimed at car radio listeners.

With the 23 other results from his culling of soul repertoires in cowboy boots, Rounce shows how Johnny Cash and other white Nashville stars had tapped into the repertoire of black Memphis soul for their country clientele. And he discovered a pattern that can be found on all four compilations: “The saxophone was used as the doyen with the soul productions. In the country realm, it’s the steel guitar that dominates.”

In his research, Rounce also revealed how both black and white studio musicians had contributed in the Tennessee music meccas of Memphis and Nashville when it came to recording albums. Label boss Roger Armstrong believes this confirms his view: “Country music is white soul music.”