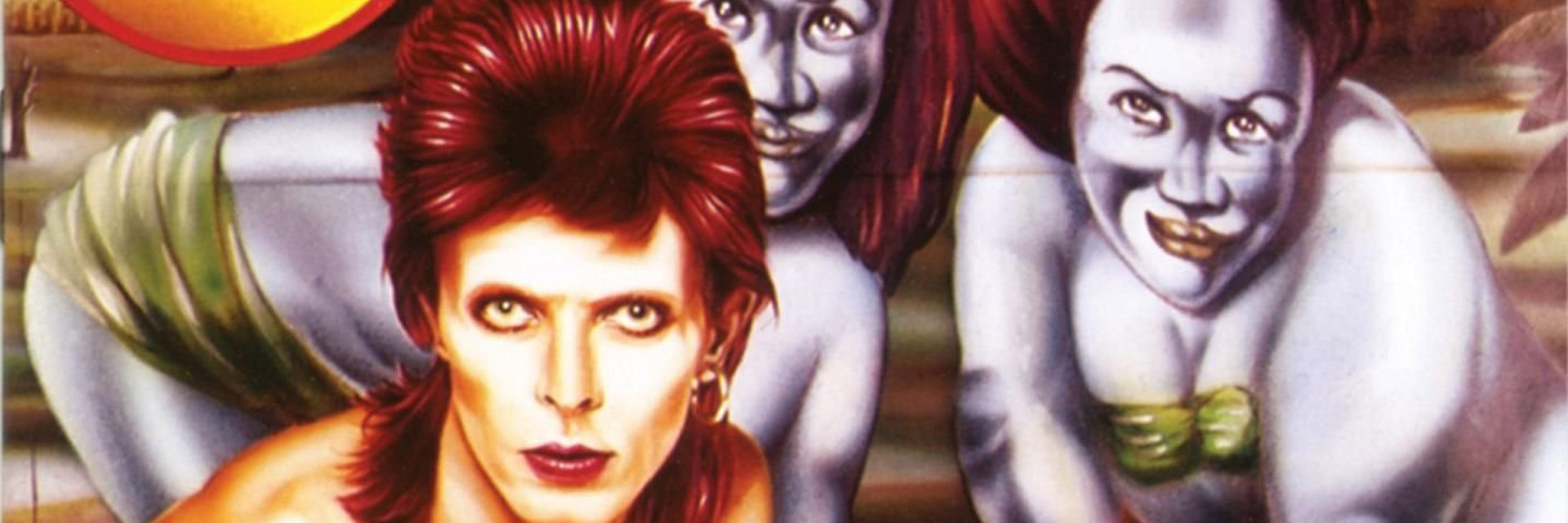

From the gaunt, alien Ziggy Stardust through solid-colored, big-shouldered suits on MTV to a philosophical album about death at the end of his life, David Bowie had so many personas that he seemed to live along several parallel paths. One thing he never stopped being was an absolute original.

Text and pictures from Copper magazine issue 150

FIDELITY cooperation with Copper magazine

Read this article also in Copper

The London native, born in 1947, grew up loving American rock and roll. Soon he learned to plunk out Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley tunes on ukulele and piano. In his teens, his stepbrother introduced him to the world of modern jazz and beat poetry. Bowie’s characteristic response was to start learning the saxophone. Throughout his life, there was no aspect of the arts that he wasn’t eager to try his hand at.

Using his real name, Davie Jones, he and his band the King Bees released the single “Liza Jane” in 1964. Because the single went nowhere, he moved on, becoming lead singer for the Manish Boys. They made a single of the blues song “I Pity the Fool,” which they learned off a Bobby Bland record. He tried a couple more bands, but nothing blossomed. Plus, people were getting him confused with the Monkees’ Davy Jones.

His solo debut was the perfect time to change his name. David Bowie came out in 1967. When it tanked, Bowie got so frustrated that he turned his energy to studying mime and avant-garde theater techniques. However, he kept writing songs and managed to sell a few to other artists. Hoping to restart his music career, Bowie put out another album called David Bowie in 1969. Although its sales were disappointing, it is now recognized for its interesting melding of psychedelia, folk, jazz, and rock. But a single succeeded where the album failed. A week before NASA launched Apollo 11, Bowie released “Space Oddity.”

A less well-known track on that second album is “Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed.” Its stream-of-consciousness lyrics and use of acoustic guitar and harmonica sometimes gets it compared to Bob Dylan. But the psychedelic meandering of the melody is as much steeped in Jefferson Airplane as Dylan. (Surrealistic Pillow had come out two years before.)

At this point, Bowie decided he needed his own, dedicated band. When the drummer John Cambridge proved hard to work with, Bowie hired Mick Woodmansey. Mick Ronson played guitar, and Tony Visconti, who was also producing, played bass. The Man Who Sold the World (1970) was their first effort together; with its turn toward hard rock, it was not appreciated at the time. Poor sales weren’t helped by the fact that Mercury Records released no singles from it until more than a year later.

The marketing team did no better with Hunky Dory (1971), although the single “Changes” would subsequently grow into a hit. This album finds Bowie in a state of experimentation, from wearing dresses in interviews to acknowledging his admiration of Lou Reed in the song “Queen Bitch.” Meanwhile, he was busy building on Reed’s proto-punk lyric and melodic style, blended with the wild freedom of Iggy Pop, to create Ziggy Stardust.

The world met this otherworldly being in The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), which Bowie supported with an intensely theatrical stage show. He became glam rock personified. As for the music, Bowie took Reed’s conversational, introspective style and heightened it to something ethereal.

Visconti had left the year before, so Ken Scott produced and Trevor Bolder played bass.

The big single was the melodious “Starman,” whose flip side, “Suffragette City,” also got a lot of play. But the album opener, “Five Years,” deserves a fresh listen for its quietly complex syncopation in doo-wop harmony, plus some distinctive imagery in the lyrics: “My brain hurt like a warehouse/It had no more room in there…”

Bowie continued the hyper-theatrical style for Aladdin Sane in 1973, but needed a break from living as a split personality by the end of the year. The result was an album of 1960s covers, called Pin Ups. His next original collection, Diamond Dogs (1974) provided the huge singles “Rebel Rebel” and “Diamond Dogs.” Visconti came back to produce.

That album was inspired in part by Orwell’s novel 1984, which Bowie wrote about in the song by that name. It’s an unusual application of soul and funk rhythms and textures to serious, apocalyptic lyrics.

The soul and R&B influences were deeply entrenched in the songs of Young Americans (1975). By this point, Bowie’s star was ascendent; singles like “Young Americans” and “Fame” took over the airwaves.

Gripped by an addiction to cocaine, Bowie was frantically creative in the mid-1970s, mining the electronica, art rock, and Krautrock genres for a brainier, more outré sound, which he perfected on the 1976 masterpiece, Station to Station. Produced by Bowie himself and Harry Maslin, this philosophical record brought into the world the Thin White Duke persona. Beyond the hits “Golden Years” and “TVC15,” the track “Stay” exemplifies this new blending of forward-looking technology and intellectual exploration, still underpinned by a soul sensibility.

There was no slowing his popularity, even when he relocated to Berlin to get clean. The result of that migration was the so-called Berlin Trilogy, comprising Low (1977), Heroes (1977), and Lodger (1979).

One of the most fascinating tracks in that whole trilogy is “Yassassin (Turkish for: Long Live).” The title comes from the Turkish verb meaning “may he have a long life.” Bowie combines a reggae beat with vaguely Middle-Eastern melodic ideas, largely thanks to the violin contributions of Simon House.

The 1980s continued Bowie’s popularity boom. The inception of MTV brought him a whole new audience: he was a natural at providing captivating visuals for his music. There isn’t space here to dissect that decade’s work in detail, but the output included Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) from 1980, Let’s Dance (1983), Tonight (1984), and Never Let Me Down (1987).

Playing with the band Tin Machine and getting married kept Bowie from doing much solo work for a few years. Black Tie White Noise (1993) finds him providing saxophone on tracks inspired by everything from his wedding to the Rodney King trial in Los Angeles. This album got him back on a regular release schedule, putting out an album every couple of years for the next decade. A highlight was Earthling (1997), which shows strong elements of electronica and industrial rock. “Battle for Britain (The Letter)” has a frenetic, grungy energy in the accompaniment, starkly contrasted with the placid melody.

After the album Reality (2003), Bowie took a ten-year break from making records. Or so it appeared. Then, without warning, he released The Next Day in 2013. Recorded in secret and co-produced with Tony Visconti, its first single, “Where Are We Now,” became Bowie’s last Top 10 hit.

There was something extraordinary about how Bowie brought his career to the perfect stopping point just as he was dying, exemplifying the intelligent control he maintained over his work throughout his career. First, there’s the satisfying fact that Blackstar (2016) was his 25th studio album. And then there was the connected project, Lazarus, a “jukebox musical” developed by New York Theater Workshop with Bowie’s in-person participation (despite already knowing his grim diagnosis).

As for the Blackstar album, which contributed the title song in Lazarus, Bowie created some of the most startling and moving songs of his career. For example, here’s “Girl Loves Me”:

There’s no denying it: Bowie was great right up to the end.

Special thanks to Copper magazine