There’s a recurring figure in jazz history: the young, heroic trumpeter who suffered a tragic death much too early on in his career.

Bubber Miley, Bix Beiderbecke, Bunny Berigan, Sonny Berman, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Joe Gordon and Booker Little are all famous examples of this figure. Not to forget Lee Morgan, of course. Recording his first album at the age of 18, Morgan already seemed to have become a giant among modern trumpet players. His 1958 album Candy was probably the most mature ever recorded by a 19-year-old. Although drug abuse slowed his subsequent solo career somewhat, he regularly outshone all other colleagues in his sessions with Art Blakey. In 1963, Lee Morgan made a comeback as band leader on the Blue Note label—and what a comeback it was. The Sidewinder became the best-selling album Blue Note had ever released, and marked a real turning point.

The reason for this was the title track, or, more precisely, the rhythm of this track. It could be regarded as Swing or even Latin, but most interpreted it as a dance track with a funky eight-eighths groove. “The Sidewinder” marked the transition from gospel-inspired hard bop to soul-inspired hard bop. In essence, it’s simply a blues number with 24 measures to each chorus instead of the usual 12, plus a few playful breaks. Also released on two sides of a single record, the track quickly became a jukebox hit. This success enabled the album to peak at number 25 on the U.S. pop LP charts in early 1964. For the small, independent Blue Note jazz label, things were never the same again—and it came under pressure by distributors to produce similar hits. The laid-back record business suddenly became a risky proposition. Reeling from this success, the producer Alfred Lion sold Blue Note to a pop record company in the following year. His co-founder Francis Wolff stayed with the label for a while longer until his stress-related death in 1971. Shortly afterwards, Lee Morgan himself, the trumpeting great, was shot dead on the street by his common-law wife. He was 33 years old.

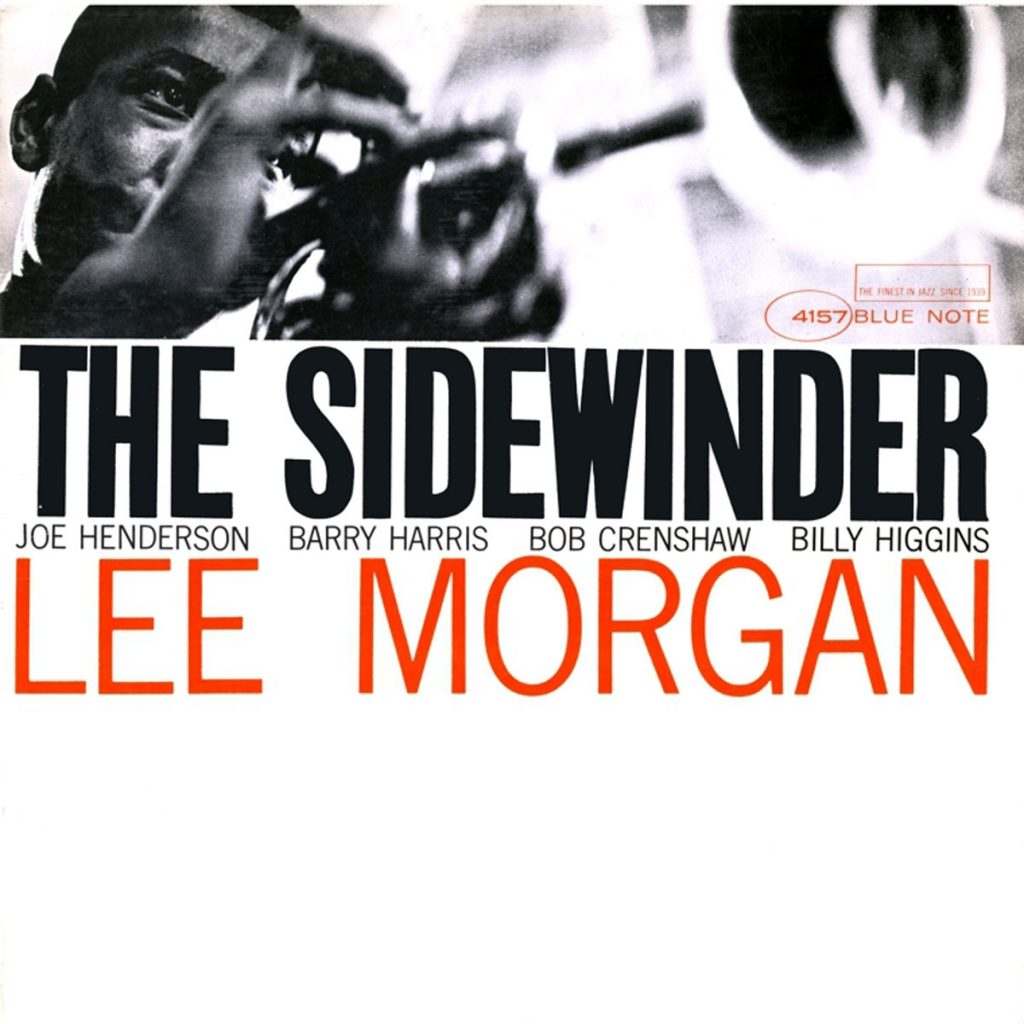

Naturally enough, the 1964 album cover has become a Blue Note classic. The top third features a photo of the musician (Francis Wolff was the photographer)—a black and white picture stretching across the entire width of the cover. The central strip looks like a banner headline, with the name of the album and the musicians, in black and red. The lower third has been left completely white. Reid Miles was the designer of this and many other distinctive Blue Note covers in the 1950s. He developed the two-color look—four-color printing was expensive in those days. He came up with several pretty similar covers such as those for Stanley Turrentine (Hustlin, 1964), Bobby Hutcherson (Stick-Up, 1966), Cecil Taylor (Conquistador, 1966) and McCoy Tyner (The Real McCoy, 1967). But The Sidewinder always remained something special, a symbol of success and tragedy at the same time. And definitely a cover with a high recognition factor.

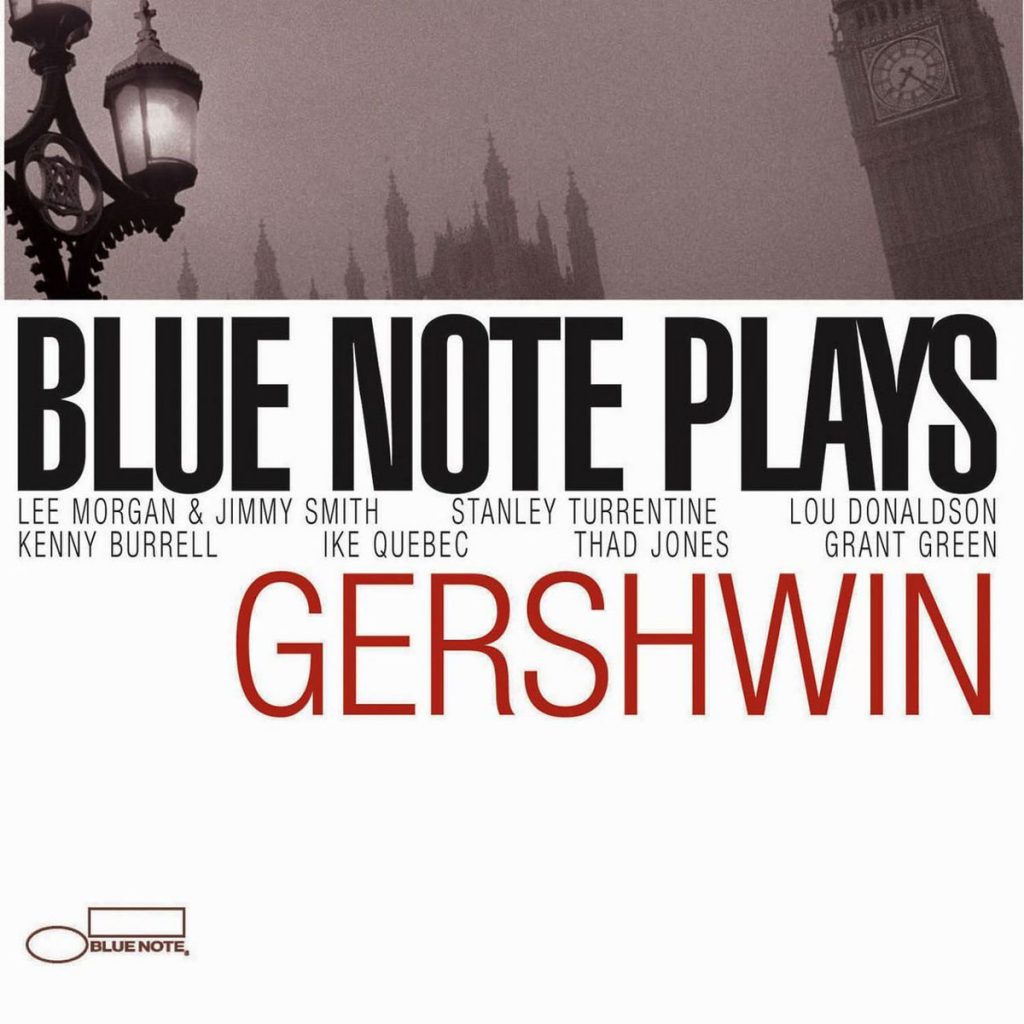

So it’s no real surprise that Blue Note has subsequently used the cover (owned by several different companies in the meantime) as a model for a whole series of CDs. Between 2004 and 2006, eleven compilations were released in the Sidewinder design as part of the Blue Note Plays series — all tribute albums to great artists and containing cover versions from the Blue Note catalog. The artists who were honored in this way range from Cole Porter to Sting, and from Gershwin to Prince. To some extent, this choice of artists also determines the age and style of the compilations. The jazz versions of the Prince and Sting songs originate predominantly from the 1990s, and the Stevie Wonder, Burt Bacharach and Ray Charles compilations mainly from the 1970s. The last albums in the series (from 2006) are all dedicated to well-known standard jazz numbers, and dominated by the classical Blue Note sound of the late 1950s.

On Blue Note Plays Gershwin, for example. Instead of a photo of the musician, the cover shows the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben shrouded in London fog. In the foreground, there’s a street lamp standing on Westminster Bridge. Gershwin fans, of course, will think immediately of “A Foggy Day (In London Town)”, a Gershwin song from 1937. In this recording from 1961, alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson plays it at a pretty fast-moving pace, accompanied by electric organ, electric guitar and drums. In fact, there’s quite a lot of organ and guitar on the entire album: there was presumably an electro fan involved. On the Lou Donaldson track, “Baby Face” Willette plays the organ; on other numbers it’s Freddie Roach or Jimmy Smith. Guitarists Grant Green and Kenny Burrell both make two appearances on the album, once as band leader and once as sideman. Burrell’s solo version of “But Not For Me” (1956) forms the centerpiece of the album, but he also plays on the first track “’S Wonderful”, so taking us nicely back to our trumpet prodigy Lee Morgan. Morgan was 19 years old when he soloed on this studio recording from 1957. It took until the 1980s, however, before it was finally released by Japanese jazz enthusiasts. Here he is once more. The king of modern trumpet-playing, a youthful hero and a brilliant artist who came to a tragic end.