Jörn Janczak makes no compromises for the sound, design and craftsmanship of his extraordinary hi-fi creations. After visiting his exceptional company Tidal, we came away with deep insights into his philosophy.

For aficionados of premium audio equipment, the term “high-end” is associated with an exclusive band of devices: chrome units from Berlin, champagne-colored machines from Japan and stunning black boxes from North America, just to name a few. But Hürth doesn’t bring much to mind, does it? Yet that’s exactly where a trailblazing manufacturer of high-end audio equipment set up shop, surrounded by TV studios and production companies. But the founder, owner and mastermind behind Tidal and Vimberg, Jörn Janczak, prefers a more understated approach. Rather than beat his drum loudly, declaring the magnificence of his hi-fi systems for some media coverage, Janczak lets them speak for themselves — that is if you’re lucky enough to experience it. On a beautiful spring day near Cologne, we met to do just that.

Separated from time and space

And here I am — in a huge, and yet subtly optimized listening room. While the sound modules aren’t hidden, a double take’s required to realize the purpose of the cleverly placed decorative elements. The utter silence of the room conveys its exquisite quality. A wall of speakers stands proud before me. The noble Akira is present, framed by La Assoluta mono power amps, the Presencio preamp, a D/A converter and a few skilfully laid cables. In my hand rests a large tablet that gives me access to an almost endless number of songs. “Have some fun, turn it up,” said Jörn Janczak before he left the room. “I have to take care of a few phone calls upstairs, it will take a minute.” You don’t have to tell me twice. But where to begin? Classic, folk, jazz, the audiophile standards? Akira is staring at me with her ten black eyes, and I can almost imagine her thinking: “What’s taking you so long?”

So, I’m alone with a hi-fi chain that many high-end fans would give their right arm to test, and I can’t decide on the music? After nine, ten swipes of the screen, my eyes rest on the familiar cover of Feist’s Metals album. “The Bad in Each Other,” that always works. One moment later and the crisp electric guitar is ringing around the room, soon followed by Leslie Feist’s gentle voice that holds a slightly nasal, nearly metallic allure. Perhaps the tonal impact intentionally underscores the album title? But that’s not my thought in the moment. Rather, I am captivated from the very first note: Akira lets me feel the Plektron gliding across the strings of the guitar, none of the intricate strokes escape me. Without warning, the wall behind the chest-high speakers becomes as nonexistent as the five meters between me and the diaphragm surfaces — hardly twenty seconds have passed, and I am already part of the music.

My hesitation has been snuffed out. Next, comes the light-blue cover of Dead Can Dance’s Dionysus. Compared to Feist’s excellent Metals, this album is produced to audiophile standards — despite the slightly less than subtle use of compressors. Though they are a creative stylistic device: The intro, “Sea Borne,” celebrates a waltzing rhythm, evolves over six minutes and finally unfolds into a kind of hypnosis. But the groove doesn’t just come from the percussion. Immense compression harmonizes instruments, drums, a choir, various samples and synth textures into a unified wall of sound that floods the listening room while holding incredible depth. Akira pumps the frequencies to my position with perceptible force — and I am hardly even listening that loudly. Enormous bass billows casually through the room with incredible ease, while each note from Lisa Gerrad’s “Yangqin,“ a Chinese version of the zither, pierces the sonic tapestry like pinpricks, lending an illusion of dynamics to the compressed recording.

Jumping from album to album, title to title, my selections unintentionally grow more obscure. After a brief intermezzo with Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, I indulge in Prodigy‘s big beat hymn “Smack My Bitch Up,” then detour through Chelsea Wolfe’s “We Will Hit The Wall,” before landing on an electronic number from Boards of Canada. I’m lost in Jamie XX’s strangely fascinating bass revelry “Gosh” when my colleague Schulz pops his head through the door and asks me blankly what I’m listening to. I had to pull myself together for a moment before I could truthfully answer: “Uh…music?”

My “five minutes” easily became a more than one-hour parkour of listening. And I listened to every song, and I mean every song, in its entirety, which is more than unusual for these kinds of situations. My colleague was taking pictures on the floor above me and became an involuntary witness to my escapades as I steadily increased the volume.

Right behind him, this unique system’s creator entered the room, and I could tell by his grin that I’m far from the first person to completely lose track of time, space and, ultimately, themselves, while enjoying the system.

Precision Engineering

“Several years ago, I saw a documentary about the production of luxury Swiss watches,” Jörn Janzcak had told us earlier in the day. “It showed how the craftsmen filed and polished the drilled holes that stay hidden deep inside the watch. Totally crazy, no one will see them.” We discussed the high-quality craftsmanship of his products, which have become true obsessions over the years. He recognized himself in this documentary, because his own products are also thoroughly crafted down to the last detail. But it was a long road to achieve such perfection. “In the beginning,” he says, “we just tried to make good speakers.” In the small room next to us, packed with photography equipment, stands a direct impression of the early stages of his work — his first Piano model. He eventually turned it into an open cutting pattern, and while this hip-height draft is impressive enough, it can barely be compared to the precise craftsmanship of today’s models.

The skilled toolmaker established the company in 1999 together with his childhood friend Swen Wasserrab. “WBE – We build emotions“ was their business’ planned name, still visible on the nameplate of the halfopen Piano. But they decided the phrase was too soft. Janzcak suggested “Tidal” and used the original name as a conceptual subline. He was inspired by Fiona Apple’s album by the same name, which remains one of his favorites to this day.

“Our first speakers were already quite sophisticated and fully sufficient to convince the lenders. But we lacked a meaningful concept,” Janczak recalls. His partner eventually left Tidal, though they still maintain a friendship, and so he planned for his next steps: Along with an excellent sound, his speakers would have a timeless design and, above all, secondto-none craftsmanship.

We all know that looks are a matter of taste. But anyone eyeing Janczak’s masterpiece La Assoluta would agree that a speaker could hardly look more beautiful. Composed of three pieces, and almost two-and-a-half meters tall, the speaker is definitely bulky, but its well-balanced proportions and sloped edges soften any concerns that might arise with other sound sculptures in this weight and size category. This virtue is also shared in the smaller models such as the Akira and Agoria. Of course, such a sophisticated design doesn’t happen by chance. Janczak brings us to an unassuming computer running CAD software, wherein we can see the housing design of a bass shaker for the car hi-fi segment. It’s a glimpse into Tidal’s past — the founding duo got their start sound tuning car systems, but “…just making it louder, louder and even louder was not our goal,” recalls Janczak. Together, they developed a fondness for uncompromising sound quality and started correcting delays in retrofitted chasses. The Tidal speaker models also originate on the computer: “This way, I can plan and modify, position in artificial space, tailor their proportions to the surroundings and work out details without wasting a bit of wood.”

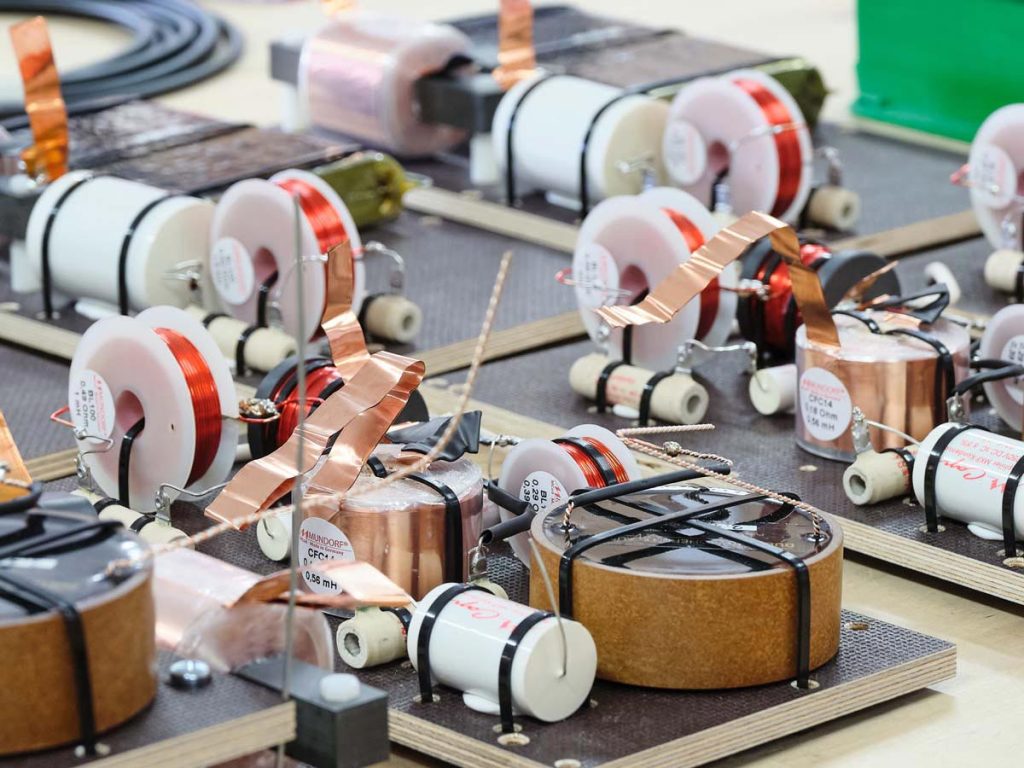

An hour later, we discover his near obsession with perfect workmanship. But to find it we drove a short way through Hürth, away from the TV studios, over to a small industrial park and into an unassuming courtyard where we found ourselves before the door of a medium-sized, modern hall. Once inside, the atmosphere was notably relaxed. Employees of Jörn Janczak – only three of them here today — are working on upcoming orders, cleaning work surfaces, counting parts and manufacturing smaller assemblies with chaotic braids of tiny wires. One of the workers warned us of the hall’s “terrible beast” lurking in the corner. This turned out to be a curious little red-haired dachshund. “All of the steps involved in assembling our speakers take place in these two rooms.” And standing in the middle of the room, not to be overlooked, are a pair of freshly minted La Assolutas, waiting patiently to be expertly packaged. Meanwhile, the work areas are producing crossovers equipped with the finest components imaginable; individual parts and a collection of old prototypes sit on the surrounding shelves.

In a separate room, a worker is polishing the final coating of a Vimberg Tonda. Tidal‘s perceives the recent off-shoot as something like the more-affordable alternative to the established portfolio. These are speakers priced too low and produced in quantities too large to belong to the manufacturer‘s exclusive brand of products. “Volume production was never our goal,” says Janczak. His primary focus are the customized, one-off productions and craftsmanship. Though, naturally the Vimbergs are also absolute dream crossovers that carry a good deal of Tidal DNA: “The actual housing of the Tonda is made of several layers of material,” explains the unit’s proud creator. “The lacquer plays an important role with my speakers. We use it almost like an armor, a dampening insulation.” The Tonda receives an impressive 35 kilos of polyester lacquer in three application steps. And even after drying and sanding, the lacquer still accounts for a substantial share of the “little” speaker’s 100 kilograms. As for the immense La Assoluta, an astounding 90 kilograms are applied three times to each speaker.

Utterly fascinated, we inspect the satin finish. The waiting Assoluta’s dual real wood veneers shimmer through crystal clear lacquer, creating a striking perception of depth. By changing your vantage point, the fine wood grains beneath the insulating layer seem to dance like flames. “It is difficult enough to make a speaker like the Tonda in this quality. And it gets even more tricky to maintain this craftsmanship for the next 40 units.” In an earlier interview, Janczak discussed how he had once planned to give a La Assoluta to anyone who could show him a better lacquer finish. That statement might seem arrogant, but after looking at the production, we now understand his justifiable pride — and, as far as we know, he hasn‘t had to make good on his promise.

Sound that can be planned

On one side of the production tables lay several chasses, all Accuton models. “They have a reputation for being the best drivers available,“ explains Janczak. “For me, they are simply components that will be incorporated into a more complex context.” Later on, at company headquarters again, he shows us measurements of the precious basses, diamond mid-ranges and tweeters. Suddenly we understand what he means: For the combined price of all eleven chasses fitted into one La Assoluta, you could buy three pairs of the smaller Contriva. That’s as exclusive as it gets. And, gauging by that, the frequency responses at first seem sobering. “That’s pretty good…you should see other drivers.” Without hesitation, Janczak lets us watch while he fine tunes the system — all of his sound concepts are composed on the computer. For a moment, the tinkerer and inventor shine through in Janczak, a man so naturally neat and focused: “This is how it would look with these filter components, and like this with the others . . . and you could also tune them like this. I really shouldn’t show you this yet, but it’s incredibly exciting.” We follow along on the big screen, our eyes growing wider as we watch frequency responses light up, measurements and sketches of crossovers and material studies and the plans for the different prototypes and future projects. “You need to keep your cool for optimal sound tuning. Frequency response and timing behave like fire and water — it is difficult to get them to cooperate. Finding a speaker‘s configuration through trial and error is like a game of chance.”

On my way home, I wonder how such a rational and objective developer can create such vibrant and emotionally encompassing systems. After my previous day’s sound journey through the sophisticated Tidal system, I’m sure it will be a while before I can take my own system seriously again. And Jörn Janczak’s holistic approach might be to blame. Tidal has long been free of its sometimes difficult early days as purely a speaker producer. Today, along with the incomparable speakers, his company makes a full line of electronics and cables. Every screw fitting, detail of his preamp and power amp is planned by Janczak with exactly the same meticulous attention he uses to build his dream crossover. And just before I left, he showed me how carefully even the tiniest wires are laid between the assemblies in an open Assoluta monoblock — I could only think of the Swiss watchmaker. The level control of the associated preamp is produced with soundless network switching, which takes an astounding four circuit boards. “We took an immense step forward with the electronics,” he explained. “This means that details such as cables become calculable parameters whose behavior can be predicted, just like the behavior of the crossover assemblies.” In a field that practically breathes by adorning itself with terms like “emotion” and vivid “goosebumps,” his approach seems surprisingly matter-of-fact, if not downright rational. But it is precisely this concentrated planning that becomes the final product and, as far more than the sum of its parts, mesmerizes the listener within mere moments, spiriting them away on a sonic journey.

www.tidal-audio.com

www.vimberg.de